Table of Contents

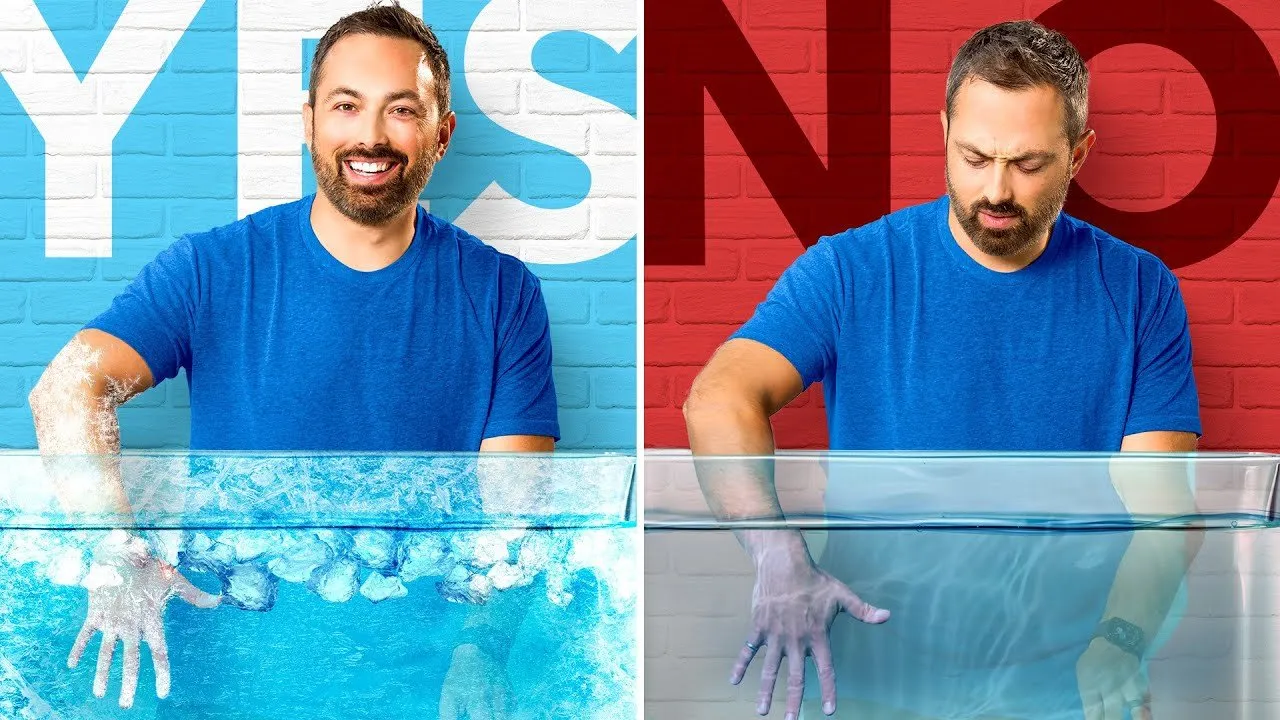

Imagine submerging your hand into a bucket of freezing water. It stings, your fingers go numb, and every instinct screams at you to pull away. Now, imagine you have to do it twice. In the first trial, you keep your hand in 14-degree Celsius water for 60 seconds. In the second, you endure the exact same 60 seconds, but keep your hand in for an additional 30 seconds as the water warms ever so slightly to 15 degrees. Common sense dictates that the first option is superior; it involves less total pain. Yet, when presented with this choice in controlled experiments, the vast majority of people voluntarily choose the second option: more pain.

This baffling phenomenon isn't a glitch in human masochism; it is a fundamental feature of how the human brain encodes memory. Replications of psychological experiments initially conducted by Daniel Kahneman and Barbara Fredrickson reveal a cognitive quirk that influences everything from medical procedures to how we judge the quality of a human life. By understanding the mechanisms behind why we prefer "better endings" over "less pain," we can hack our own psychology to improve our long-term happiness.

Key Takeaways

- The Two Selves: We possess an "experiencing self" that lives in the moment and a "remembering self" that evaluates the past, and their interests often conflict.

- Duration Neglect: The total length of an experience has almost no impact on how we rate it retrospectively; we prioritize intensity over duration.

- The Peak-End Rule: Our memories of an event are dominated by two specific points: the moment of peak intensity and the very end of the experience.

- Practical Application: You can improve the memory of unpleasant tasks (like workouts or medical exams) by artificially adding a mild, "less painful" ending.

The Cold Hand Paradox

To understand the disconnect between actual experience and remembered experience, researchers replicate the famous "Cold Hand" study. Participants submerge their hands in freezing water in two distinct trials, rating their discomfort in real-time. Unbeknownst to them, the trials are rigged.

The first trial is straightforward: 60 seconds of pain. The second trial subjects the participant to the same 60 seconds, followed by an extra 30 seconds where the water warms by one degree. While still painful, this final segment is slightly less excruciating than the peak.

When asked which experience they would prefer to repeat, nearly 70% of participants in the original Kahneman and Fredrickson study chose the longer trial. Even when participants verbally acknowledge that the choice makes no sense—admitting they are choosing more total suffering—their gut instinct pushes them toward the trial with the "better" ending.

"The choice I made doesn't seem to make much sense... You endured discomfort for longer. But at the end, the discomfort reduced a little bit."

This reveals a startling psychological truth: the "experiencing self" (who felt the pain) is overruled by the "remembering self" (who recalls the narrative). For the remembering self, a longer duration of pain is acceptable if the narrative arc of the pain concludes on a downward trend.

Duration Neglect and The Camera of the Mind

Why does the brain discard the element of time when evaluating an experience? This cognitive bias is known as duration neglect. Whether an unpleasant medical procedure lasts 10 minutes or 20 minutes, or a vacation lasts one week or two, has surprisingly little effect on our retrospective happiness or unhappiness.

Research involving video clips further validates this. When students watched pleasant videos (puppies playing) or unpleasant ones (medical amputations) of varying lengths, the duration of the clip had almost no impact on their retroactive rating of the experience. The brain does not record experiences like a continuous film reel; instead, it operates more like a photographer.

"Memory doesn't make films, it makes photographs." — Milan Kundera

These "photographs" capture the most salient moments—specifically the peaks of emotion and the final moments. This relates to the representativeness heuristic, a mental shortcut where we judge a whole by its most representative parts rather than a mathematical average of the entire experience.

The Representativeness Heuristic

Our brains constantly look for patterns and shortcuts. We judge probability based on how well an example matches our mental models rather than raw statistics. This is famously illustrated by the "Linda Problem," where people mistakenly believe it is more probable for a woman named Linda to be a "feminist bank teller" than just a "bank teller" because her description matches the prototype of a feminist.

Similarly, when we look back on a vacation or a relationship, we don't calculate an average of every minute spent. We recall the highlights (the peak) and the conclusion (the end). These representative moments color the entire memory, rendering the duration irrelevant.

Recency Bias and The Quality of a Life

The "End" component of the Peak-End Rule is driven largely by recency bias. We assign greater importance to recent events because they are freshest in our neural pathways. This explains why a fantastic TV series can be "ruined" by a lackluster finale. The ending doesn't change the enjoyment experienced during previous seasons, yet it taints the memory of the show entirely.

This bias is so potent it affects how we judge the value of a human lifespan. In a 2001 study, participants evaluated the life of a fictional character named Jen.

- Scenario A: Jen lives a happy, fulfilling life for 30 years and dies instantly in an accident.

- Scenario B: Jen lives the same 30 happy years, followed by 5 additional years that are pleasant but not "great."

Rationally, Scenario B represents more total happiness (30 great years + 5 good years). However, participants consistently rated Jen's life in Scenario B as less desirable. The addition of "merely okay" years at the end diluted the "average" happiness of her life story. In the eyes of the remembering self, a short, perfect life is often viewed as superior to a long, slightly diluted one.

Hacking the Peak-End Rule

While these heuristics can lead to irrational choices, understanding them offers a powerful toolkit for improving our lives and the lives of others. By manipulating the "end" of an experience, we can alter how it is remembered.

Improving Medical Outcomes

In a landmark 2003 study, Kahneman applied this theory to colonoscopies. For one group of patients, the procedure ended normally. For another group, the physician left the scope in place for an extra three minutes without moving it—creating a period of discomfort that was lower than the peak pain of the procedure.

The results were counter-intuitive but consistent with the theory: patients who endured the extra three minutes rated the entire experience as 10% less unpleasant. More importantly, they were significantly more likely to return for follow-up screenings. By adding unnecessary but lower-intensity discomfort, doctors improved long-term health outcomes.

Optimizing Daily Experiences

We can apply the Peak-End Rule to design better memories for ourselves and others:

- Exercise: If you push yourself to failure on a hill sprint and immediately stop, your memory of the workout will be defined by that agony. Instead, engage in a pleasant cool-down walk. The lower intensity at the end will trick your brain into remembering the workout as less grueling, making you more likely to exercise again.

- Customer Experience: This is why IKEA places cheap hot dogs and ice cream right after the checkout counters. The fatigue of shopping and paying is mitigated by a positive "end" experience, ensuring you remember the trip fondly.

- Vacations: Do not obsess over the length of the trip. Focus your budget and energy on creating one massive "peak" experience and ensuring the final day is relaxing and pleasant.

- Social Exits: Whether leaving a job or a party, your final interactions will disproportionately influence how people remember you. Being extra kind and gracious in your final weeks at a job can overshadow years of average performance.

Conclusion

Our brains are not impartial recorders of history. We are storytellers that prioritize drama and conclusions over accuracy and duration. While this can lead to logical fallacies—like choosing more pain over less—it also provides a blueprint for satisfaction.

We cannot always control the duration of our hardships or the intensity of our struggles. However, we often have control over how experiences end. By engineering "soft landings" and positive conclusions, we can fool our remembering selves into viewing difficult experiences with a kinder lens, ultimately building a happier narrative of our lives.