Table of Contents

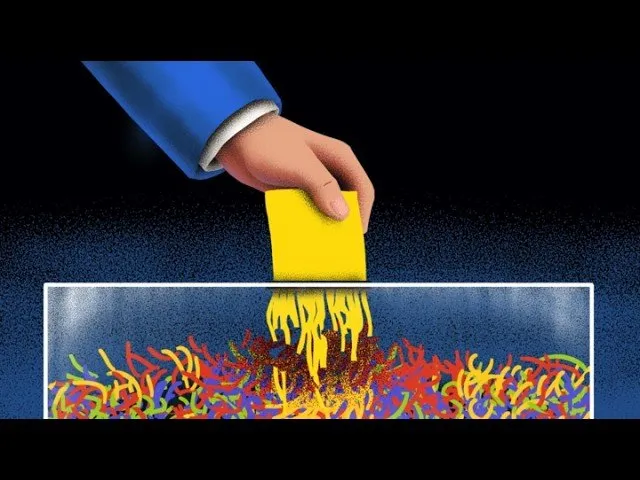

The suggestion that democracy might be mathematically impossible sounds like a cynicism born of frustration. However, this is not a comment on human nature, political corruption, or the historical instability of civilizations. It is a statement of logic. The current methods used to elect leaders in many major democracies are fundamentally irrational, a conclusion supported not by opinion, but by well-established mathematical proofs that have led to a Nobel Prize.

This article explores the mathematics behind decision-making, the inherent pitfalls of our most common voting systems, and whether a truly fair election is merely a theoretical dream.

Key Takeaways

- First Past the Post (FPTP) often results in minority rule and forces voters to vote strategically rather than honestly due to the "spoiler effect."

- Ranked Choice Voting, while an improvement, suffers from paradoxes where a candidate performing worse can actually trigger their victory.

- Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem proves that no ranked voting system can simultaneously satisfy five basic criteria for fairness without resulting in a dictatorship.

- Approval Voting offers a mathematical loophole by switching from ranking candidates (ordinal) to rating them (cardinal), potentially solving the major logical flaws of democracy.

The Flaws of "First Past the Post"

The most common voting method, used by the United States and 43 other countries, is "First Past the Post" (FPTP). The premise is simple: voters select one candidate, and whoever gets the most votes wins. Despite its simplicity and history dating back to the 14th-century House of Commons, it is mathematically brittle.

The primary issue with FPTP is that the winner does not require a majority—only a plurality. This frequently leads to situations where a party holds 100% of the power despite a majority of the citizenry voting against them. In the last century of British politics, a single party held a majority of seats in Parliament 21 times, yet in only two of those instances did they secure the majority of the popular vote.

The Spoiler Effect

FPTP also creates the "spoiler effect," where similar parties steal votes from one another, inadvertently helping their ideological opposite win. The 2000 US Presidential election serves as the textbook example. In Florida, George W. Bush defeated Al Gore by fewer than 600 votes. However, Ralph Nader, a Green Party candidate positioned to the left of Gore, received nearly 100,000 votes.

The mathematics suggest that the vast majority of Nader voters preferred Gore over Bush. Had they been able to express a second preference, Gore likely would have won. Instead, by voting for their favorite candidate, they helped elect the candidate they liked least. As noted in the analysis of the event:

"Most of those voters were devastated that by voting for Nader rather than Gore, they ended up electing Bush. In a first past the post system, they had no way of expressing that preference."

This dynamic forces voters to abandon their honest preferences and vote strategically for the "lesser of two evils." Over time, this consolidates power into two massive parties, a phenomenon known as Duverger's Law.

The Paradox of Ranked Choice Voting

To solve the spoiler effect, many reformers advocate for Instant Runoff Voting, also known as Ranked Choice Voting or Preferential Voting. In this system, voters rank candidates from favorite to least favorite. If no one secures a majority (50% + 1), the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated, and their ballots are redistributed to those voters' second choices. This process repeats until a winner emerges.

This system has distinct social benefits. Because candidates hope to be the "second choice" of their opponents' base, they are incentivized to be civil. In the 2013 Minneapolis mayoral race, 35 candidates ran using this system. Rather than mudslinging, the atmosphere was so cordial that candidates literally sang "Kumbaya" together at the final debate.

When Doing Worse Helps You Win

However, Ranked Choice Voting is not mathematically immune to failure. It suffers from a counterintuitive flaw where a candidate losing support can actually cause them to win. Consider a hypothetical election between three candidates: Einstein (Left), Curie (Center), and Bohr (Right).

- Round 1: Einstein gets 25%, Curie 30%, Bohr 45%. No one has a majority.

- Elimination: Einstein has the fewest votes. He is eliminated. His supporters, preferring the center to the right, flow to Curie.

- Result: Curie beats Bohr.

Now, imagine Bohr runs a terrible campaign and loses some voters to Einstein. Logic dictates Bohr should do worse. However, the math shifts:

- New Round 1: Curie now has the fewest votes because Bohr's defectors boosted Einstein.

- Elimination: Curie is eliminated first.

- Redistribution: Curie is a centrist. Her voters split between Einstein and Bohr.

- Result: The influx of Curie's moderate voters pushes Bohr over the edge to defeat Einstein.

In this scenario, Bohr winning was contingent upon him performing worse in the first round. This violation of logic is a known failure mode of Instant Runoff systems.

The Mathematical Wall: Condorcet and Arrow

The quest for a perfect voting system is not new. In the 18th century, the French mathematician Marquis de Condorcet identified a circular logic problem now called Condorcet’s Paradox.

Imagine a group trying to choose dinner:

- Group A prefers Burgers > Pizza > Sushi

- Group B prefers Pizza > Sushi > Burgers

- Group C prefers Sushi > Burgers > Pizza

In head-to-head matchups, Burgers beat Pizza, Pizza beats Sushi, and Sushi beats Burgers. The group preferences form a rock-paper-scissors loop, meaning there is no mathematical winner. Condorcet died in prison during the French Revolution before he could resolve this, but 150 years later, Kenneth Arrow proved that a resolution might not exist at all.

Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem

In 1951, economist Kenneth Arrow published a PhD thesis that would win him the Nobel Prize. He proposed five reasonable conditions that any fair voting system must satisfy:

- Unanimity: If everyone prefers A over B, the group chooses A.

- No Dictators: No single person’s vote should determine the outcome regardless of others' preferences.

- Unrestricted Domain: The system must handle any set of voter preferences (no ignoring difficult ballots).

- Transitivity: If the group prefers A to B and B to C, they must prefer A to C.

- Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives: Introducing a third option (C) should not change the group's preference between A and B.

Arrow proved, mathematically, that for any ranked voting system with three or more candidates, it is impossible to satisfy all five conditions. Satisfying the conditions of logic and fairness inevitably leads to a scenario where a single voter dictates the outcome—a dictatorship. This is known as Arrow's Impossibility Theorem.

Is There a Solution?

While Arrow’s theorem seems to sentence democracy to mathematical incoherence, there is a loophole. Arrow’s theorem applies specifically to ranked (ordinal) voting systems. If we move to rated (cardinal) systems, the impossibility vanishes.

The Case for Approval Voting

One of the most promising alternatives is Approval Voting. In this system, voters do not rank candidates. Instead, they simply select all the candidates they approve of. You can vote for both the Green Party candidate and the Democrat, or the Libertarian and the Republican.

This method offers several advantages:

- No Spoiler Effect: You can support a minor party without fearing you are helping your ideological enemy.

- Increased Turnout: Research suggests simpler ballots encourage participation.

- Broad Appeal: The winner is the candidate acceptable to the largest number of people, favoring consensus builders over polarizing figures.

Kenneth Arrow himself, initially skeptical, eventually conceded that rated systems like Approval Voting effectively sidestep his impossibility theorem.

Conclusion

Is democracy mathematically impossible? Strictly speaking, if we rely on ranked systems, the answer is yes. Perfection is unattainable, and every ranked method requires sacrificing a condition of fairness. However, "impossible" does not mean we should settle for the flawed First Past the Post system, which is arguably the worst of all options.

Mathematics offers us better tools, such as Approval Voting or methods based on the Median Voter Theorem. While the machinery of democracy may never be mathematically perfect, it can certainly be upgraded. As Winston Churchill famously noted:

"Democracy is the worst form of government except for all the other forms that have been tried."

The math may be crooked, but it is the only game in town. The responsibility lies in understanding the rules well enough to fix them.