Table of Contents

Key Takeaways

- René Girard's mimetic theory posits that most human desire is not original but imitated (mimesis) from others (models), driving much of our behaviour.

- This imitation, especially of desire ("metaphysical desire"), leads to rivalry when individuals converge on the same scarce objects or status symbols.

- Modern society, particularly elite environments like universities, often fosters intense mimetic rivalry, leading to widespread "hollowness" and dissatisfaction despite apparent success.

- Historically, societies contained mimetic conflict through the "scapegoat mechanism," uniting against and sacrificing an often-innocent victim to restore peace.

- Girard argues that myths often encode these founding murders, told from the persecutors' perspective, justifying the violence and deifying the victim afterwards.

- Christianity uniquely reveals the scapegoat mechanism by telling the story from the victim's (Christ's) perspective, exposing the mob's deceit and the victim's innocence.

- This revelation dismantled traditional sacrificial systems but unleashed mimetic forces, channeled partly through modern institutions like capitalism and law.

- Modernity exhibits hypocrisy by persecuting perceived persecutors (privilege) in the name of victims, continuing scapegoating dynamics under a different guise.

- Girard predicted escalating global rivalry (e.g., US-China) and believed humanity is heading towards apocalypse due to unchecked mimetic conflict and nuclear weapons.

Timeline Overview

- 00:00–15:00 — Introduction to René Girard's influence by David Perell and lecturer Jonathan Bi. Bi recounts his personal journey to Girard, driven by existential hollowness and the observation of mimetic desire among peers at Columbia University, chasing prestige over genuine interest. Girard's ideas offered a "map" to understand and navigate these forces. Discussion on how Girard's theory helps avoid debilitating envy/pride situations rather than eliminating mimetic tendencies. Mimetic theory is presented as "cheaper than psychoanalysis" because it economically explains broad social phenomena beyond personal therapy.

- 15:00–30:00 — Girard's predictive power exemplified by his 2007 anticipation of US-China conflict, contrary to prevailing optimism. He saw that similarity, not difference, breeds conflict and that relative status matters more than absolute wealth. Girard's framework involves psychology (mimesis, metaphysical desire) and a philosophy of history from human origins (evolution via mimesis) to apocalypse. Overview of the 7-lecture series structure: Psychology (Lectures 2-3), History/Apocalypse (Lectures 4-7). Introduction to Girard the man: born 1923 Avignon, influenced by WWI/WWII violence and witnessing scapegoating by the French Resistance post-liberation. His unorthodox intellectual path across history, literary theory, anthropology, and theology, always somewhat an outsider. Why he's called an "exegete" (interpreter of scripture/texts) rather than philosopher/prophet.

- 30:00–45:00 — Summary of Girard's system begins: History of humanity from ape to apocalypse. Core psychological concept: Mimesis (imitation) differentiates humans from apes, not reason. Humans are uniquely prone to imitating others' desires, experiences, judgments ("co-vibrating violin strings"). Metaphysical desire (desire to be, aiming at identity/status via objects) vs. Physical desire (desire to experience, aiming at utility/pleasure). Metaphysical desire often involves imitating a "model" perceived to have fullness of being, adopting their desires (e.g., "Be Like Mike" ads). This "triangular desire" (Subject-Model-Object) is humanity's strongest drive, leading to obsession. Romance is a key example where desire is often inflamed by a rival suitor (mimetic desire).

- 45:00–1:00:00 — Girard's attack on the "romantic lie" of the authentic individual self. Even rejecting the group (negative mimesis, e.g., tech elite vs. finance suits) is socially determined, driven by resentment or a desire to show superiority, not true independence. Bi shares his personal experience oscillating between conformist startup ambition (positive mimesis) and resentful rejection of industry for philosophy/Buddhism (negative mimesis), both inauthentic. Human sociality is paramount; reason often serves as a post-hoc rationalizer for socially determined desires. Humans uniquely create myths, fictions, and die for abstractions (honor, gods), unlike "sober" animals. Moving to history: Increased human mimesis destabilized simple animal dominance hierarchies, leading to mimetic rivalry and societal collapse ("war of all against all"). Surviving groups stumbled upon the scapegoat mechanism: spontaneously converging on a victim, blaming them for the chaos, and achieving cathartic peace through their (often violent) expulsion/murder. This process is unconscious and deceitful; the victim is rarely truly responsible for the societal crisis.

- 1:00:00–1:15:00 — The scapegoat mechanism involves a second deceitful step: Deification. The expelled/murdered victim, having "magically" brought peace, is retrospectively credited with divine power—both the power to cause the chaos and the power to end it. The victim paradoxically becomes a god (e.g., Oedipus, or divinized figures like Julius Caesar). All pagan religions and cultures (including Roman Republic via Julius Caesar) are founded on these victim-turned-god figures captured in myth. From these founding murders/myths derive real institutions: Prohibitions (castes, gender roles) to create difference and slow mimetic spread, and Rituals (sacrifices, festivals) to re-enact the founding murder safely for catharsis. These systems are based on lies hidden by the myth (told from persecutor's view). Christianity represents a rupture: it tells the same scapegoat story structure (Christ's persecution) but from the victim's perspective, revealing Christ's innocence and the mob's deceit.

- 1:15:00–1:30:00 — Christianity as the "religion to end all religions" or "myth vaccine." By revealing the victim's innocence, it dismantles the scapegoat mechanism, which requires belief in the victim's guilt for catharsis. This accelerates history onto a linear path, unleashing powerful, ambivalent forces: Love (concern for victims, human rights, but also hypocritical persecution of "persecutors"), Truth (science enabled by de-sacralizing nature, but science itself can become unquestionable dogma justifying atrocities like eugenics), Innovation (freed from past worship, but can degenerate into sterile originality-at-all-costs fashion), and Violence (traditional controls removed). Modernity is plagued by hypocrisy arising from these ambivalent forces. The analogy of a rocket struggling against gravity represents modernity's tension between cultural advancement and unchanging human nature.

- 1:30:00–1:43:51 — The fourth force: Violence. Christ's message ("I came not to send peace, but a sword") aimed to dismantle the violent foundations (scapegoating) of worldly peace. By removing sacrificial mechanisms (prohibitions, rituals), Christianity took away humanity's "training wheels" for managing conflict. Modernity hasn't collapsed yet due to two temporary containments: Capitalism (channels violent competitive energies into productive, non-lethal rivalries) and Law (maintains order via threat of superior state violence). However, Law is weakest between nations (global trade), where violent energies build without a supreme arbiter. This leads to Girard's prediction of escalating conflict (US-China) and apocalypse, amplified by nuclear weapons which remove friction and ensure mutually assured destruction. Girard's final advice: Withdraw from the world's conflicts to preserve one's soul, as apocalypse is inevitable. Final warnings about the potential negative side effects of engaging with Girard's ideas: alienation, inaction due to ambivalence, and hopelessness.

Introduction: The Grip of Imitated Desire

- Philosopher René Girard profoundly impacted lecturer Jonathan Bi, revealing his entrapment in "meaningless status competitions" and desires that weren't authentically his own. This realization stemmed from observing peers miserably pursuing societal expectations rather than genuine wants.

- Girard's ideas expose the vanity of pursuits driven by social games and status signaling, offering a rescue from these often hollow endeavors. Bi emphasizes that acquiring these insights was difficult due to Girard's dense and unstructured writing style.

- This lecture series aims to present Girard's entire system in a structured, understandable way, exploring its relevance for the contemporary world over seven lectures.

- Jonathan Bi, despite a background in competitive math and computer science at Columbia, found Girard not through achievement but through "desperate existential necessity" stemming from personal suffering and failures. He argues failures are often more relevant than successes in understanding a Girardian's journey.

The Hollowness of Mimetic Rivalry

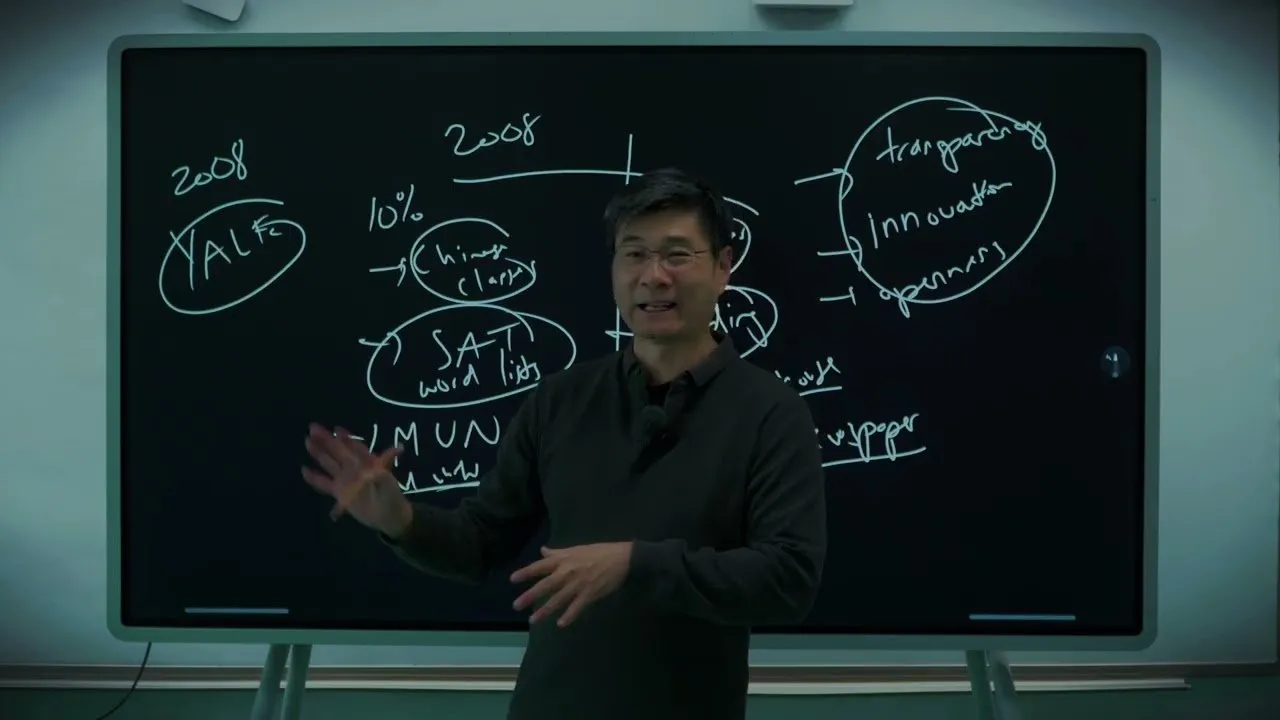

- Bi describes elite colleges like Columbia as environments filled with "hyper conscious status oriented prestige seeking teenagers," leading to a pervasive existential "hollowness".

- Students often engage in activities—supporting political causes, socializing, dating, pursuing internships—not for intrinsic reasons but due to mimesis, imitating what society or peers deem desirable. Bi notes the absurdity that 2,000 supposedly independent minds overwhelmingly converge on just four career paths (finance, tech, law, medicine).

- This pursuit requires self-deception, convincing oneself that the path of prestige is genuinely desired, often fueled by the "equally drunken rhetoric" of peers. The resulting life feels empty because even victories, like landing a prestigious internship, provide only fleeting satisfaction as they stem from imitated, not genuine, desire.

- A wake-up call came from observing alumni who had "made it" (good job, postal code, partner) but remained plagued by the same hollowness, "making money they didn't need to buy things they didn't want to impress people they didn't particularly like". This revealed the potential endpoint of a life lived according to external expectations rather than a core of genuine desire.

- Moderator David Perell shares examples: buying unaffordable fancy cars, consultants viewing director titles as salvation only to find no lasting happiness, and intense parental status competition over children's college admissions, symbolized by bumper stickers. These illustrate how mimesis makes people lose awareness of their own desire's nature.

- Bi admits he was deeply caught in these forces ("the most mimetic of them all"), realizing with fright he could live his entire life fundamentally not for himself. Girard's work offered salvation, akin to Virgil guiding Dante, by exposing the origins and terrifying consequences of desire.

Navigating Mimesis: Awareness, Not Immunity

- Girard's ideas don't grant immunity to mimesis; Bi states he's "just as susceptible to mimetic forces as I was before". The practical benefit lies in gaining foresight and judgment to avoid situations that trigger destructive envy or pride.

- Using John Boyd's analogy: superior fighter pilots use judgment to avoid situations requiring superior skill. Similarly, Girardian awareness helps construct social environments and choose relationships that minimize exposure to toxic mimetic contagion, rather than providing power to resist it once deeply caught.

- The value of engaging Girard isn't just therapeutic ("cheaper than psychoanalysis"); it's that his theory accurately reflects fundamental, often overlooked or hidden, truths about the human condition.

- Mimetic theory is more "economic" than frameworks like Freudian psychoanalysis; Girard explains phenomena like the Oedipus complex through the simpler, broader assumption of imitative desire leading to rivalry, rather than an innate desire for the mother. This allows Girard's theory to explain a vast range of psychological, social, and historical patterns.

- Girard's insights provide a unique "map" to see opportunities and dangers others miss. Example: His contrarian 2007 prediction of deteriorating US-China relations, based on mimetic principles.

- He rejected the premise that shared economic benefits (cheaper goods) would ensure goodwill, understanding humans prioritize relative status over absolute gain. America would feel unsettled by a closing gap with China, even if richer overall.

- He rejected the premise that increasing similarity fosters harmony, arguing instead that similarity (desiring the same things) increases the surface area for competition and conflict.

- Girard stated: "a conflict between the United States and China will follow... trade can transform very quickly into war... the dispute is between two forms of capitalism that are becoming more and more similar". Fifteen years later, this proved depressingly accurate.

The Scapegoat Mechanism: Violent Foundations of Culture

- Girard posits that mimesis, specifically the imitation of desire ("metaphysical desire"), destabilized early human groups by causing desires to converge across dominance hierarchies, leading to rivalry and societal breakdown ("war of all against all").

- Societies that survived stumbled upon the "scapegoat mechanism": in moments of crisis, the group unconsciously converges on a single victim (or small group), blames them for the chaos, and restores unity and peace through their collective expulsion or murder. This process is spontaneous and deceitful, not rational deliberation.

- Historical examples include Socrates' trial, witch hunts during the Black Death, Nazi scapegoating of Jews, and McCarthy-era persecution. Humans seem to need a single, radical source of evil to blame for complex problems.

- This founding murder, though based on a lie and morally wrong, was brutally effective at restoring order and was essential for the formation of lasting cultures, according to Girard. It worked because humans are "spirited animals" driven by vengeance, pride, and envy, needing cathartic release against a perceived evil, not rational solutions.

- A second stage of deceit follows: Deification. The peace descending after the murder seems miraculous, so the crowd retrospectively credits the (now dead) victim with divine power—both the power to cause the chaos and the power to end it. The victim paradoxically becomes a god.

- Pagan gods (like Oedipus, or divinized figures like Julius Caesar) embody this dual nature of being responsible for destruction and salvation, reflecting their origin as scapegoated victims. Myths encode these events, always from the persecutors' perspective, justifying the violence.

- From these founding events and myths, two types of institutions arise to maintain order:

- Prohibitions: Rules creating social difference (castes, gender roles, lineages) to slow the spread of mimetic desire and prevent rivalry.

- Rituals: Controlled re-enactments of the founding murder (sacrifices, festivals) to provide cathartic release and reinforce social cohesion.

Christianity's Revelation and Rupture

- Christianity appears structurally similar to pagan myths (unrest, scapegoating of Christ, divinization, mythologization via Bible, institutionalization via Church). So why does Girard consider it true and paganism false?

- The crucial difference: Christianity is the first story told from the perspective of the innocent victim, not the persecuting mob. Pagan myths (e.g., Oedipus, Romulus/Remus) always justify the violence, affirming the victim's guilt from the crowd's viewpoint.

- The Gospels explicitly declare Christ's innocence (even by Pilate), portray the mob as arbitrary and deceitful, and reveal the charges as projections. The story is told by disciples (victim's side).

- Christianity thus acts as a "myth vaccine," using a similar structure but revealing the truth of the scapegoat mechanism – the victim's innocence and the mob's collective delusion. This exposure fundamentally undermines the mechanism, which requires belief in the victim's guilt to function.

- This revelation dismantles the sacrificial foundations of pagan culture. Once the victim is known to be innocent, catharsis fails, peace isn't mysteriously restored, deification loses its basis, and the prohibitions/rituals lose their sacred authority.

- Christianity shifts history from cyclical time (based on repeated sacrificial crises) to a linear trajectory, unleashing powerful, ambivalent forces.

Modernity's Ambivalence and the Path to Apocalypse

- Christianity unleashed four key forces shaping modernity: Love, Truth, Innovation, and Violence. These forces are ambivalent, often manifesting in hypocritical ways.

- Love: Led to humane institutions (law, human rights, concern for poor/dispossessed). However, it fuels new forms of persecution ("persecution of persecutors") where privilege itself becomes the target of scapegoating in the name of victims. Girard warns: "Our society’s obligatory compassion authorizes new forms of cruelty".

- Truth: Enabled science by de-sacralizing nature and freeing inquiry from myth/magic. But science itself can become a deified dogma ("scientism"), silencing dissent and justifying political agendas (e.g., eugenics, flawed climate predictions), just as religion once did. Appealing to "science" becomes a conversation stopper.

- Innovation: Freed humanity from blind worship of the past, enabling progress. But the modern "rage for originality" paradoxically stifles real innovation by rejecting necessary imitation and mastery. It degenerates into sterile fashion and "negative imitation". Girard notes how historically, great innovators (Goethe) and industrial powers (Germany, US, Japan) began as imitators.

- Modernity is thus characterized by hypocrisy: persecution in love's name, dogma in truth's name, conformity in innovation's name, all while the underlying human need to scapegoat persists.

- Violence: Christianity dismantled the scapegoat mechanism, humanity's primary tool for containing violence. While Christ intended love, removing sacrificial controls ("training wheels") without changing human nature allows mimetic conflict to escalate unchecked. Christ foresaw this: "I came not to send peace, but a sword".

- Modernity hasn't collapsed yet because violence is temporarily channeled/contained by:

- Capitalism: Redirects competitive, honor-seeking energies from warfare to economic rivalry (making better products/services). It's driven by spirited desires (glory, prestige), not just utility or greed.

- Law: Maintains order through the state's monopoly on violence, preventing private vengeance cycles.

- The system is most fragile where these intersect weakly: global trade between nations. Here, competitive energies flare without a supreme legal authority, leading Girard to predict escalating conflict (US-China trade war).

- The invention of nuclear weapons makes this global rivalry apocalyptic. Nukes remove friction, forcing instant, total, mutually assured destruction (MAD) at the first sign of conflict, unlike past warfare. We narrowly avoided catastrophe during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

- Girard believes apocalypse is imminent and unavoidable. His only advice is personal withdrawal from the world's conflicts to nurture one's soul, as the kingdom of God is not of this earth.

René Girard's mimetic theory provides a sweeping framework for understanding human desire and conflict, arguing that imitation drives rivalry, which societies historically managed through scapegoating. Christianity revealed this violent foundation, inadvertently unleashing forces that, combined with modern weaponry, place humanity on an accelerating path toward potential apocalypse.