Table of Contents

The Iliad is not merely an epic poem; it is the bedrock of Greek civilization and, by extension, the foundation of the Western world. It is historically fascinating that a single work of literature could birth a culture that produced Plato, Thucydides, and Sophocles. To understand how a poem constructs a civilization, we must look beyond the narrative of the Trojan War and examine the philosophical and rhetorical mechanisms at play. By exploring the Greek concepts of virtue, the reality-bending power of speech, and the insights of Immanuel Kant and Percy Shelley, we can see how the poet functions not just as a storyteller, but as the ultimate creator of reality.

Key Takeaways

- Arete and Eudaimonia: Greek civilization was built on the pursuit of excellence (Arete) and the flourishing that comes from fulfilling one's potential (Eudaimonia), whether in war or speech.

- Speech as Reality Construction: In the Iliad, rhetoric is a form of combat where the speaker projects a new "movie" or reality onto the audience to compel action.

- The Kantian Shift: Immanuel Kant’s philosophy suggests we are active participants in shaping reality through time and space, with language acting as the primary tool for this ordering.

- The Poet as Prophet: According to Percy Shelley, poets act as conduits for the divine "Geist" or universal memory, creating the values and narratives that sustain civilization.

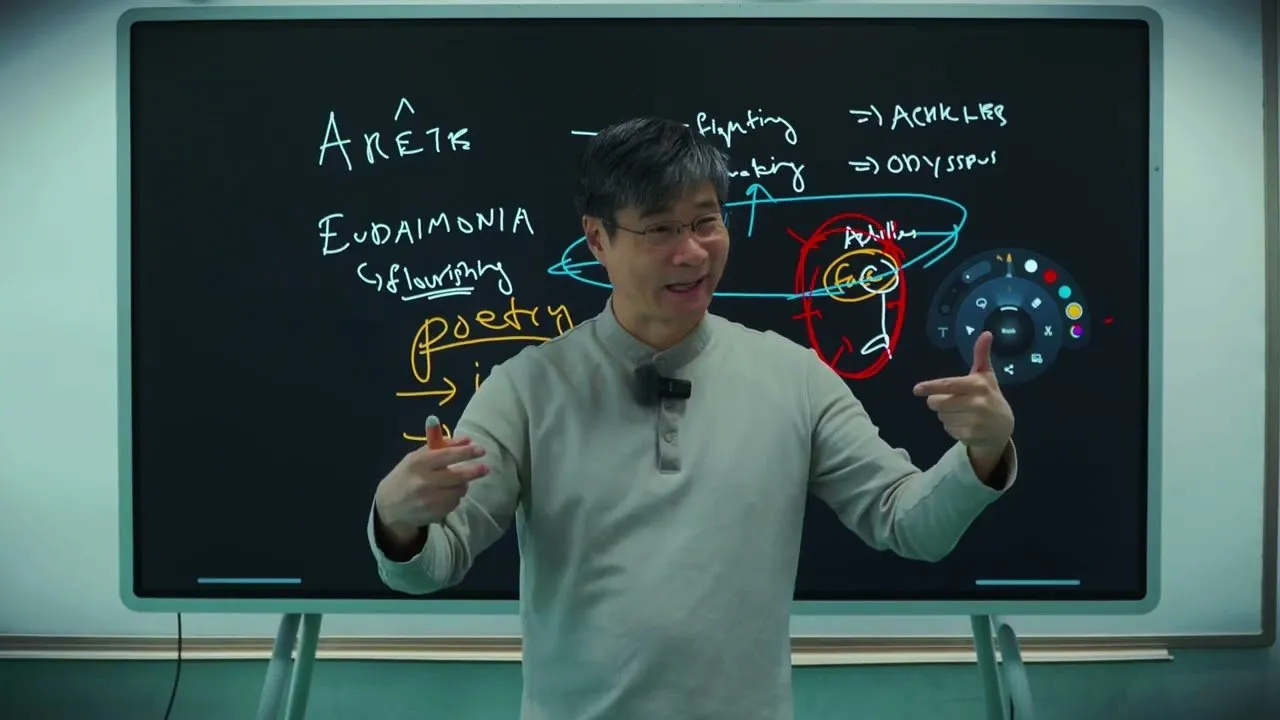

The Twin Pillars of Greek Character: Arete and Eudaimonia

To grasp the psychology of the Iliad, one must understand two central concepts: Arete and Eudaimonia.

Arete translates to virtue, excellence, or character. It is the specific quality that makes an individual exceptional. In the Greek tradition, this excellence manifests primarily in two arenas: war-fighting and speech-making. Achilles stands as the paragon of the warrior, while Odysseus represents the supreme orator. While these seem like distinct skills, the Greeks viewed them as two sides of the same coin.

Eudaimonia is often translated as happiness, but it more accurately means "flourishing." It suggests that a person can only achieve true contentment when they are expressing their Arete to its fullest potential. This explains the tragic choice of Achilles:

"He could either die old at home or die young but a hero on the shores of Troy... Of course, I'm going to die young in Troy because only by fighting, only by winning glory can I achieve udimonia."

When Achilles sits out of the fighting due to his dispute with Agamemnon, he is miserable not just because of the insult, but because he is denied the ability to be Achilles. Without the expression of his excellence, human flourishing is impossible.

Rhetoric: The War of Realities

If war is the imposition of one’s will through physical force, speech-making is the imposition of one’s reality through beauty and truth. In the Iliad, speeches are often incredibly long. This is not poor editing; it is a demonstration of how characters attempt to construct a narrative that others must inhabit.

Consider the embassy to Achilles, where Odysseus attempts to persuade the sulking hero to return to battle. Odysseus does not simply offer a transactional bribe. Instead, he attempts to expand Achilles' imagination. He uses imagery to transport Achilles:

- To the present: Visualizing the destruction of the Greeks and the god-like dominance of Hector.

- To the past: Reminding Achilles of the promises made to his father, Peleus.

- To the future: Painting a picture of the glory and riches that await him upon victory.

Odysseus creates a "movie" aimed at changing Achilles' emotional reality. Achilles, however, counters with a speech that contracts reality, focusing intensely on the self ("I," "me," "my"). This clash demonstrates that speech-making is a battle for narrative dominance. The Greeks memorized these speeches not just for their beauty, but to learn the art of imprinting oneself onto the world. This mastery of language is the precursor to democracy, where governance is achieved through persuasion rather than brute force.

Kant and the Architecture of Perception

How does language actually shape reality? The German philosopher Immanuel Kant provides a framework for understanding this in his Critique of Pure Reason. Kant challenged the traditional view that humans are passive observers of an objective reality. Instead, he argued that we are active participants.

Kant distinguished between two worlds:

- The Noumena: The objective reality, or "things in themselves." This is the raw energy or vibration of the universe which we cannot perceive directly.

- The Phenomena: The "things to us." This is reality as filtered through the human mind.

We filter the Noumena through the lenses of Time (sequence) and Space (sensation). These concepts exist inside us, not outside. Because we cannot process pure energy, our minds impose order upon it. Crucially, the mechanism we use to control and share this perception of time and space is language.

Therefore, those who master language—the poets—are the ones who define reality. By creating a beautiful language that is internalized by the population, the poet creates a shared universe. Homer did not just describe Greek culture; by giving the Greeks a shared language and narrative, he literally created their civilization.

The Poet as Prophet and Legislator

If language constructs reality, where does the poet get their language? In A Defense of Poetry, the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley argues that poets are, in essence, prophets. They possess a divine connection to the universe—what Hegel might call the Geist (spirit), Jung the "collective unconscious," or Plato the "realm of forms."

Shelley suggests that the universe serves as a divine repository of memory. Poets act as antennas, channeling these eternal truths into the material world. When Homer composed the Iliad, he was summoning living memories from this universal consciousness. This connects the audience to the divine:

"Poetry redeems from decay the visitations of the divinity in man... It creates a new the universe after it has been annalated in our minds by the recreation or impressions blunted by reiteration."

The Role of Tragedy

This connection to the divine is often mediated through tragedy. Greek drama follows a pattern: a character of great status is undone by hubris (arrogance), leading to a downfall. The audience, witnessing this, experiences:

- Epiphany: A realization of human limitations and the dangers of arrogance.

- Catharsis: A purging of emotions, resulting in a cleansed, more empathetic moral state.

Through this process, poetry and drama become mirrors. They allow us to see the divine and the tragic within ourselves. Shelley famously concluded that "poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world." They may not write the laws, but they shape the opinions, values, and imaginations from which laws spring.

Conclusion

The Iliad is a living memory. It acts as a portal that allows the reader to bypass the limitations of their immediate time and space and connect with the eternal human experience. When we read the great books, we are not just analyzing literature; we are increasing the "bandwidth" of our connection to the universal consciousness.

Homer created a civilization by projecting a reality so potent that it ordered the chaos of the world into a coherent, shared existence. By understanding the link between language, perception, and the divine, we realize that we are not passive inhabitants of the world, but active creators of it—guided by the words of the poets.

![This Bitcoin Opportunity Will Set Up Many Crypto Traders For Success! [ACT NOW]](/content/images/size/w1304/format/webp/2026/01/bitcoin-short-squeeze-opportunity-100k-target.jpg)