Table of Contents

Most of us intuitively understand the stated purpose of school. Ideally, it exists to foster literacy, develop core competencies like critical thinking and collaboration, and instill a habit of lifelong learning. In an era of rapid technological advancement and artificial intelligence, the ability to adapt and learn continuously is paramount. Yet, an objective look at the global education system reveals a stark contrast between these ideals and the reality of the classroom. Instead of fostering creativity, many schools inadvertently teach students to despise learning. To understand why this dysfunction persists, we cannot simply look at curriculum or funding; we must analyze education through the lens of Game Theory.

Key Takeaways

- The Divergence of Goals: While schools claim to teach critical thinking and literacy, systemic incentives often prioritize rote memorization, compliance, and short-term performance.

- The Principle of Least Effort: In Game Theory, every stakeholder—from students to administrators—is motivated to achieve the best possible result with the least amount of work.

- The Role of Stakeholders: The "game" of school is defined not by educational ideals, but by the converging interests of parents, teachers, and administrators, which often align around "face," convenience, and risk avoidance.

- The Superstructure Effect: Macro-societal factors like economic wealth and inequality shift a society’s focus from cohesion and openness to individualism and competition, negatively impacting school culture.

The Broken Promise of Modern Education

The theoretical mission of schooling is threefold: literacy (deep reading and writing), competency (critical thinking and cooperation), and the desire to learn forever. However, data and anecdotal evidence suggest that most schools are failing in these metrics. In many universities, professors are discovering that students no longer possess the attention span to read full books, forcing a curriculum shift toward short excerpts and videos.

Furthermore, the environment of school often actively works against collaboration. By ranking students and grading on curves, education becomes a zero-sum game. Students learn that for them to succeed, their peers must fail. This fosters a competitive, rather than collaborative, mindset. Perhaps most damaging is the impact on lifelong learning. In high-pressure systems, such as the one seen in parts of East Asia, the end of high school is often celebrated by literally burning books—a symbolic rejection of the "burden" of learning.

"Most schools not only do not teach you these skills, but they have the opposite effect. In fact, they make you hate learning."

If the system is failing its primary directive, we must ask why. The answer lies in analyzing the hidden incentives of the players involved.

A Case Study in Failed Reform

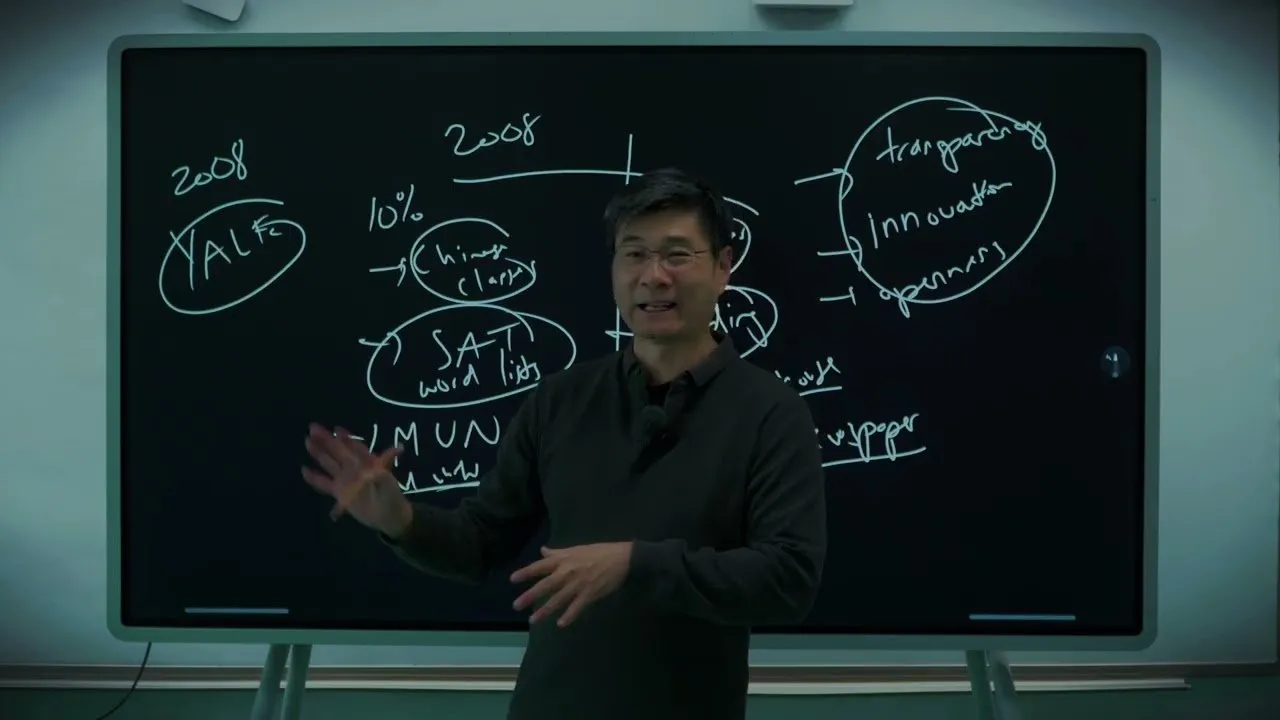

To understand the resistance to change, consider a case study from 2008 in Shenzhen, China. A reformer attempted to overhaul a traditional school program to better prepare students for top American universities. The changes were objectively sound: replacing rote vocabulary memorization with reading seminars, introducing student-run businesses (a coffee house) to teach entrepreneurship, and establishing a daily newspaper to foster transparency and writing skills.

The results were statistically undeniable. The students from this program gained admission to Ivy League institutions and developed genuine resilience. Yet, despite the success, the reformer was fired, and the program was dismantled. Why? Because the reformer was viewed as a "dictator" for insisting on meritocracy.

In the existing game, powerful parents and stakeholders did not want a fair playing field; they wanted a system they could control to ensure their children's success regardless of effort. This illustrates a core tenet of Game Theory in education: Innovation is often punished if it disrupts the established equilibrium of the stakeholders.

"The game is not fair. The game is established by stakeholders and they play the game according to their interest."

Mapping the Players and Their Real Motivations

In any game, you must identify the players and understand their true payoff structures. In the school system, the key players are students, parents, teachers, administrators, government bodies, and colleges. A naive analysis assumes these groups are motivated by "learning" or "excellence." A Game Theory analysis reveals a different driver: The Principle of Least Effort.

The Student’s Game

While we like to imagine students are driven by curiosity, their actual incentives prioritize social standing and parental approval. Students want to be popular, and they want to minimize friction with the adults in their lives. Grades are not viewed as a feedback mechanism for learning, but as a currency to purchase freedom from parental nagging. If they can achieve the desired grade with minimal effort (or cheating), the game theory optimal move is to do so.

The Parent’s Game

Parents are often the most powerful players. While they claim to want independent, successful children, their behavior often suggests a desire for control and "face." In many international contexts, education is treated as a luxury good. Parents may choose schools based on superficial markers of prestige—such as the presence of Western teachers or expensive facilities—rather than pedagogical quality. They want the badge of a top-tier university admission for their child to boost their own social status among colleagues and relatives.

The Educator’s and Administrator’s Game

Teachers and administrators are rational actors with families and bills. In a low-trust or bureaucratic environment, their incentive is to "get by." For an administrator, the primary goal is not educational revolution, but risk management. Making powerful parents happy ensures job security. Admitting mistakes or trying experimental teaching methods introduces risk. Therefore, the dominant strategy is to maintain the status quo and hide difficulties.

"Everyone wants to achieve the best results by doing the least amount of work possible. People are lazy and people are greedy. It's that simple."

The Convergence Point and Social Superstructure

A "game" is constructed when the interests of these various players converge. Currently, in many private and international school systems, the interests converge around a specific, dysfunctional equilibrium:

- Marketing over Substance: Schools invest in visible assets (buildings, foreign staff) to please parents looking for prestige.

- Grade Inflation: Teachers give easy grades to keep students happy and parents quiet.

- Compliance: Governments and administrators prefer schools that produce compliant citizens rather than disruptive innovators.

This convergence is heavily influenced by the superstructure of society—the demographics, economy, and culture. We can analyze a society's potential for education through three metrics: Cohesion, Openness, and Energy.

In developing societies or those with high social cohesion (like Finland or 1980s China), education is viewed as a collective ladder up. Teachers are respected, and students are hungry to learn because the payoff is tangible. However, as a society becomes wealthier and more unequal, cohesion fractures. Education becomes a commodity. The hunger to "work hard" is replaced by a desire to utilize wealth to bypass competition. When the superstructure shifts toward individualism and consumerism, schools inevitably transform into businesses that sell credentials rather than competencies.

Conclusion

Game Theory teaches us that the dysfunction of schools is not an accident; it is the logical outcome of the current incentive structures. Players—whether they are parents seeking status, colleges seeking tuition, or students seeking the path of least resistance—are acting rationally within the rules of the game.

Reforming education is not merely a matter of changing the curriculum or hiring better teachers. It requires a fundamental understanding of the "convergence point" where stakeholder interests meet. True reform can only happen if we shift the incentives, perhaps by moving the game away from zero-sum competition and superficial prestige, back toward a model where the genuine acquisition of skill is the only winning strategy.