Table of Contents

There is a peculiar paradox in the behavior of ambitious students and elites from rising global powers, particularly from Asia. Many spend years mastering English, obsess over obtaining US dollars, and aim to immigrate to Western nations. This strategy often appears counterintuitive. In their home countries, these individuals frequently possess high social status, strong family connections, and distinct advantages. By moving to the West, they often trade this prestige for a playing field that is structurally rigged against them—where political power and the highest corporate echelons remain largely inaccessible.

Why trade being a captain of industry at home for being a mid-level engineer abroad? The answer lies not in simple aspirations for "knowledge" or "internet access," but in the architecture of the global operating system itself. This system, a specific "game" of finance and power, was not designed by the United States, though they enforce it today. It was engineered by the British Empire. Understanding why the world works the way it does requires tracing the lineage of global finance back to the collision of empires, the invention of national debt, and the creation of the offshore banking system.

Key Takeaways

- The British Model of Empire: Unlike the resource-rich but stagnant Spanish Empire, the British and Dutch built power through commerce, piracy, and sophisticated financial systems.

- The Sovereignty of Debt: The creation of the Bank of England shifted debt from the monarch to the nation, creating the world's first true safe haven for capital.

- Protection of Property: Western legal systems were designed to protect private property regardless of its origin, effectively incentivizing global elites to move wealth offshore.

- Soft Power Indoctrination: Elite education systems (like Oxford or the Ivy League) serve to align international elites with Western cultural and financial interests.

- The Cycle of Decay: The West is now suffering from "over-financialization," mirroring the decline of the Spanish Empire by becoming insular, arrogant, and reliant on financial extraction rather than production.

The Tale of Two Empires: Hubris vs. Hunger

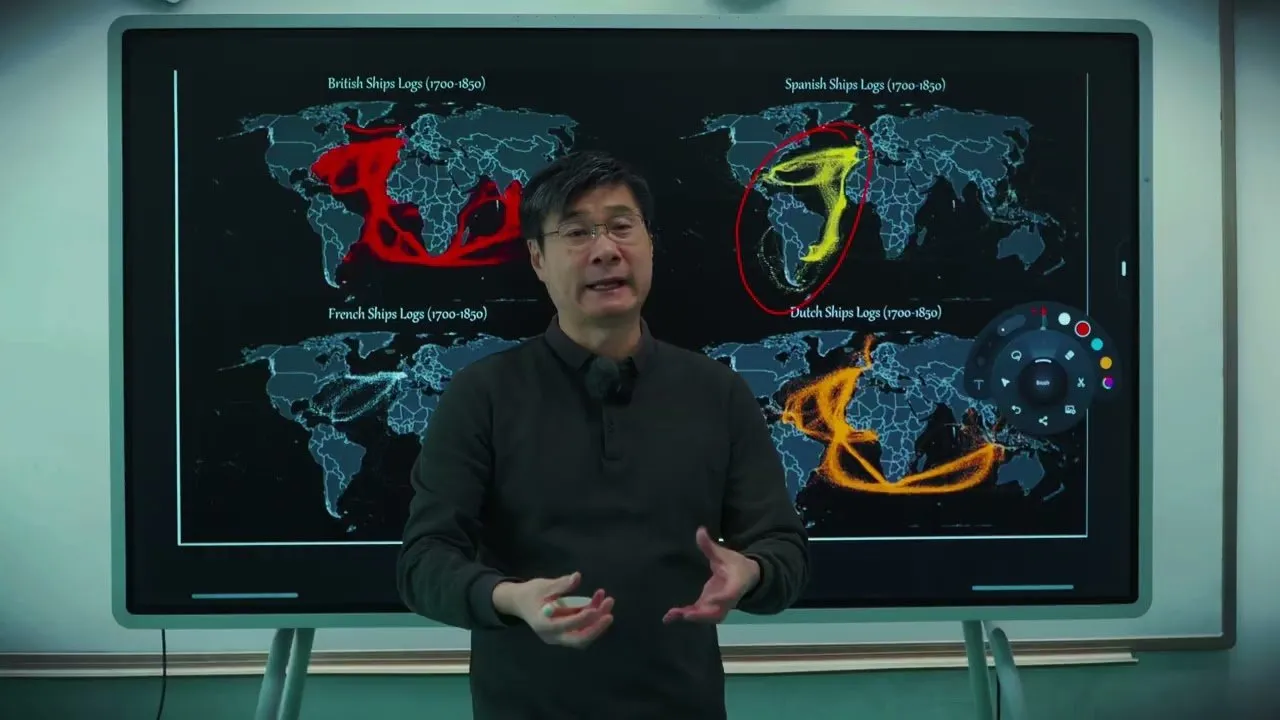

To understand modern global finance, we must look at the divergence between the Spanish Empire and the rising powers of Northern Europe (the Dutch and the English) during the Age of Discovery. Spain, at its height, controlled vast territories and extracted immense wealth, particularly silver, from the Americas. However, this easy wealth proved to be a curse.

The influx of resources made the Spanish elite lazy, insular, and arrogant—a condition historically referred to as hubris. Because they could buy whatever they needed, they stopped producing. They subcontracted their industry and shipping to other nations. They became convinced of their invincibility, fighting wars on multiple fronts and overextending their reach. The abundance of silver didn't build a sustainable economy; it built a complacent one.

The Protestant Work Ethic

In contrast, England and the Dutch Republic were resource-poor. They could not rely on extraction; they had to rely on trade, innovation, and state-sponsored piracy. This necessity forged a different cultural psychology, deeply influenced by Calvinist (Protestant) theology which viewed hard work and wealth accumulation as signs of divine favor.

While Spain remained Catholic—focused on obedience to authority—the Protestant nations became energetic, open, and socially cohesive out of necessity. They developed a middle class that was commercially aggressive. Over time, the hungry merchant nations began to outperform the wealthy but stagnant aristocratic empires.

The Financial Revolution: Creating the Safe Haven

The turning point in global history—and the birth of the modern "game"—was the Glorious Revolution of 1688. This was not merely a political shift; it was a merger of Dutch capital and British naval security. When William of Orange moved from the Dutch Republic to the English throne, he brought with him the financial sophistication of the Dutch, seeking protection from the ravages of continental wars.

This union birthed two critical innovations that underpin the modern world: the Bank of England and the concept of Sovereign Debt.

From Royal Debt to National Liability

Prior to this revolution, lending money to a king was a high-risk gamble. If the king died or simply refused to pay, the lender had no recourse. The establishment of the Bank of England changed the counterparty. Merchants were no longer lending to a monarch; they were lending to Parliament and the Nation.

"The Bank of England is really important because now you are lending money not to the king but to the nation... even though the king dies, the people are liable for the debt."

This guaranteed repayment. It transformed England into the safest place in the world to store capital. Because England was an island protected by the Royal Navy, it was physically secure from invasion. Because of Parliament, it was legally secure from arbitrary seizure.

The Sanctity of Private Property

Philosopher John Locke articulated the government's role as the protector of "life, liberty, and property." Crucially, the British legal system evolved to protect property rights without asking too many questions about the origin of that property. Whether wealth was generated through legitimate commerce or colonial exploitation, once it entered the British system, it was protected by the full force of the law.

This legal framework effectively created the world's first Offshore Financial Center (OFC). It signaled to elites across Europe and later the world: if you bring your wealth here, we will protect it, we will not ask where it came from, and we will ensure it remains yours.

Mechanisms of Global Control

The British Empire expanded not just through gunpowder, but by incentivizing local elites in colonized nations to participate in their system. This was accomplished through three pillars: finance, education, and naval dominance.

The Money Laundering Incentive

The genius of the British imperial model was that it aligned the interests of local leaders with the interests of the Empire. In places like India and China, local elites were often in conflict with one another. The British offered a compelling value proposition: help us extract resources, and we will help you secure your personal wealth abroad.

This system allowed elites to loot their own nations and transfer that capital to London or its satellite financial hubs. The legal system would "launder" this reputation, transforming money derived from drugs, corruption, or exploitation into legitimate real estate or business investments. This dynamic persists today, where elites from developing nations move capital to Western real estate markets and banks to hedge against political instability at home.

Education as Indoctrination

Hard power (the Navy) could conquer, but soft power maintained control. By establishing schools and universities in their colonies, the British created a pathway for social mobility that bypassed local hierarchies. The brightest minds were taught English, Shakespeare, and British history.

"When you learn English, you learn that British culture is superior to your local culture... you slowly come to believe that the British are superior to us."

Scholarship programs, such as the Rhodes Scholarship, were designed to identify the most talented individuals globally and integrate them into the Anglo-American worldview. These students would return home not as revolutionaries, but as administrators of the global system, convinced of the superiority of the Western model.

The Modern Offshore Archipelago

The British Empire did not disappear; it evolved. As the formal empire dissolved, it transformed into a covert financial empire. If one looks at a map of today's primary tax havens and offshore financial centers—the Cayman Islands, Bermuda, Hong Kong, Singapore, Dubai, and the Channel Islands—one finds they are almost exclusively former British colonies or protectorates.

This network facilitates the global drug trade, capital flight, and corporate tax evasion. It is a seamless system where illicit funds are moved, washed through legal structures, and reinvested in Western assets. The stability of Western markets depends heavily on this inflow of capital from the rest of the world.

This explains the "irrational" behavior of students and elites mentioned at the start. They are playing the game the British invented. They move to the West not just for jobs, but to place themselves and their assets inside the safety perimeter of the global legal and financial system.

The Trap of Over-Financialization

History, however, is cyclical. The Western world, particularly the United States and Britain, now faces the same predicament that destroyed the Spanish Empire. The immense success of this financial extraction model has led to "over-financialization."

When a society makes more money from moving capital than from producing goods, it begins to rot. The availability of easy money creates extreme inequality, political corruption, and a decline in social cohesion. The West has become, in many ways, lazy and arrogant—expecting the rest of the world to produce goods while it manages the ledger.

The Prisoner's Dilemma

If this system leads to moral decay and societal collapse in the long run, why do nations and individuals continue to play? The answer is simple game theory. In the short term, the financialized, aggressive model provides overwhelming advantages. It allows nations to fund militaries and buy influence. It is a "race to the bottom" where opting out means being eliminated.

Just as an athlete might take performance-enhancing drugs to win a gold medal despite the long-term health risks, nations play the game of financial imperialism to secure hegemony. The West is currently the victor of this game, but the very mechanisms that ensured its rise—the extraction of global wealth and the financialization of the economy—are now sowing the seeds of its internal instability.

Conclusion

The world's financial architecture is not a neutral marketplace; it is a historical artifact of the British Empire, inherited and maintained by the United States. It relies on a specific set of rules: the sanctity of capital, the use of offshore havens, and the co-opting of global elites through education and status.

While this system has generated immense power for the West, it has reached a point of diminishing returns. The "game" is rigged to favor those who control the banks and the courts, but the social and moral costs of this extraction are becoming increasingly difficult to ignore. We are likely approaching a "game reset," where the contradictions of this financial order can no longer be sustained, and a new paradigm must emerge.

![This Bitcoin Opportunity Will Set Up Many Crypto Traders For Success! [ACT NOW]](/content/images/size/w1304/format/webp/2026/01/bitcoin-short-squeeze-opportunity-100k-target.jpg)