Table of Contents

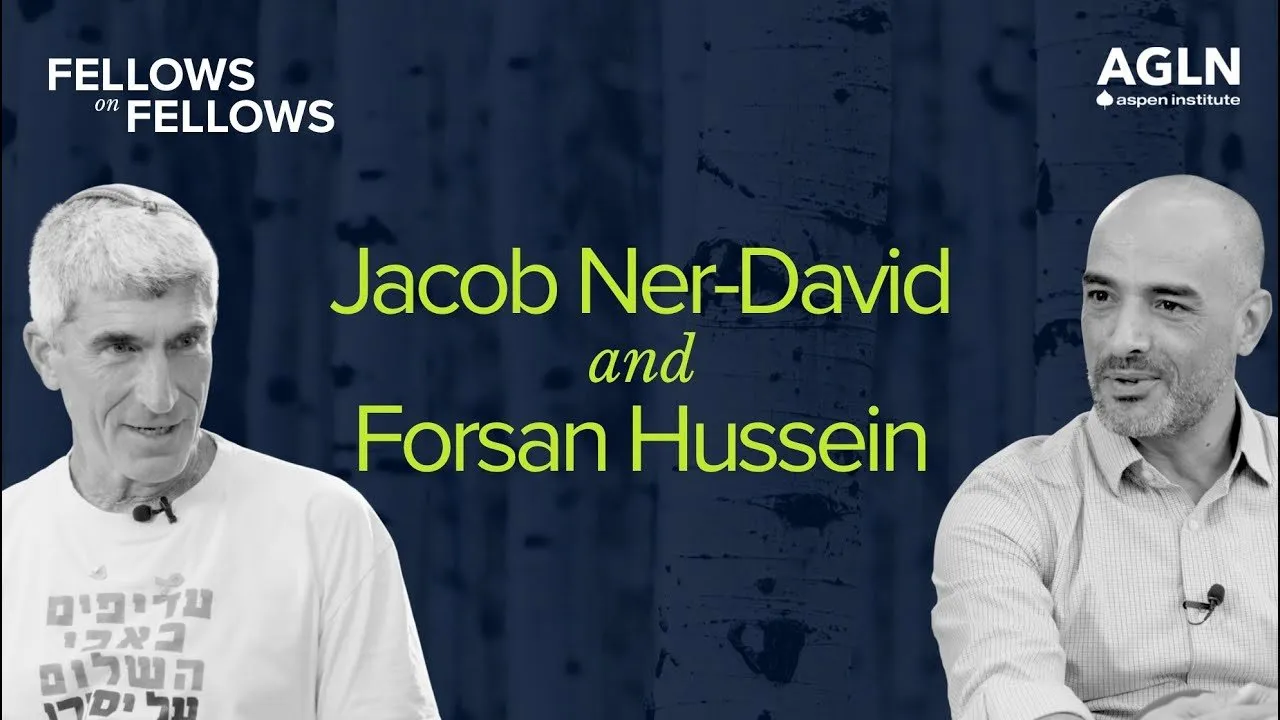

In a region defined by deep-seated conflict and historical trauma, genuine dialogue between opposing narratives is rare. It is even rarer to find a friendship that not only survives political turmoil but thrives on the shared responsibility to build a better future. The conversation between Jacob Ner-David, a Jewish Israeli-American entrepreneur, and Forsan Hussein, a Palestinian citizen of Israel and social entrepreneur, offers a powerful case study in resilience.

Their relationship, forged through the Aspen Institute’s Henry Crown Fellowship and cemented through business collaborations, transcends the typical boundaries of the Israeli-Palestinian divide. It is not a friendship based on ignoring differences, but rather on a fierce commitment to acknowledging them while prioritizing their common humanity. As the geopolitical situation grows more complex, their shared journey illuminates the difficult internal work required to maintain hope and agency.

This dialogue explores how personal narratives are reshaped, the role of economic interdependence in peacebuilding, and the heavy responsibility of leadership during times of crisis.

Key Takeaways

- Exposure Disrupts Stereotypes: Meaningful, humanizing interactions—like sharing a meal or recognizing living standards—are often the catalyst for questioning single-narrative upbringings.

- Shared Ownership of Peace: Sustainable peace cannot be imposed from the outside or by one side alone; it requires deep, shared ownership of the process from inception to execution.

- The Role of Economic Interdependence: Business ventures and technology can serve as practical bridges, creating necessary connections that go beyond political rhetoric.

- Leadership Amidst Trauma: True leadership requires resisting the urge to retreat into tribal corners during crises, instead choosing to maintain empathy and connection.

- Action Over Apathy: In the face of hopelessness, the refusal to be passive is a moral imperative. As the dialogue suggests, if you are not part of the solution, you contribute to the problem's complexity.

Breaking the Single Narrative

Most individuals in conflict zones grow up within a "single narrative," a worldview where history and justice are viewed exclusively through one's own cultural lens. Breaking out of this bubble requires not just opportunity, but the curiosity to step across invisible lines.

From Stereotypes to Humanization

For Forsan Hussein, growing up as a Palestinian citizen of Israel meant navigating a landscape where physical proximity to Jewish neighbors did not equate to social closeness. He describes a childhood where Jewish Israelis were perceived solely through the lens of military occupation and media portrayals of violence. This perspective was not shifted by a political treaty, but by a simple, human encounter.

Hussein recounts a childhood incident where he trespassed into a neighboring Jewish moshav to retrieve a lost sheep. Expecting hostility, he was instead met by an elderly man offering cookies. This moment of kindness shattered his monolithic view of the "enemy" and sparked a lifelong journey of questioning his own narrative.

"I had this image about Jews that simply came from all these stereotypes... That really changed my life because only then did I start asking questions and questioning my own narrative that really set me on that journey."

The Choice to Engage

Conversely, Jacob Ner-David’s journey involved a conscious decision to reject insularity. Despite growing up in a religious Jewish bubble in New York, he was influenced by his father’s diverse academic friendships. Upon moving to Jerusalem, Ner-David refused to adhere to the unspoken segregation of the city.

By running and biking through Arab neighborhoods, he physically traversed the lines that many ignore. However, he notes a critical distinction between observation and connection. Merely moving through a space is not enough; one must engage. This realization led him to leverage his background in entrepreneurship to forge connections that were not just social, but structural and economic.

Entrepreneurship as a Bridge

While dialogue groups are valuable, Ner-David and Hussein emphasize the necessity of "getting one’s hands dirty" through shared work. Business and technology offer unique avenues for coexistence because they rely on mutual benefit and practical problem-solving rather than purely ideological debate.

Creating Economic Interconnectivity

The duo’s history includes Zetun Ventures, a company designed to bridge Arab and Jewish economies. This approach moves beyond the theoretical "peace of the brave" discussed by politicians and fosters a "peace of the people." When individuals are economically interdependent, the cost of conflict becomes personal and financial, not just political.

Ner-David shares a compelling example from the telecommunications sector. Recognizing that the lack of a distinct country code for Palestine was a point of friction and erasure, he utilized technology to turn on a country code overnight. This was not merely a technical fix; it was an act of validating identity and dignity through business infrastructure.

The Winery and Shared Land

This philosophy extends to the Jezreel Valley Winery, where Ner-David partners with a Palestinian Christian. The very naming of the winery was a collaborative effort, reflecting a shared attachment to the land. This partnership underscores a spiritual and physical reality: both peoples are deeply rooted in the same soil.

"I believe in the fact that we're here to stay. All of us. We're not going anywhere. And the fact that if you are not part of the solution then somehow you're contributing to the complexity of the problem."

Leadership During Crisis: The Test of October 7th

The events of October 7th and the ensuing war served as a severe stress test for cross-cultural relationships. In times of acute trauma, the human instinct is often to retreat into tribalism and defensive postures. Both men acknowledge the immense difficulty of maintaining empathy when their respective communities are in deep pain.

Navigating Disappointment and Polarization

Hussein expresses deep disappointment in how quickly some alliances fractured following the attacks. He observed that many who previously championed shared values retreated into "us vs. them" rhetoric, demanding loyalty oaths rather than offering empathy. This reaction highlights the fragility of coexistence work that does not account for deep-seated trauma.

However, the response to trauma varies. Ner-David recalls the wisdom of his teacher, Rabbi David Hartman, who noted that one’s reaction to terror depends entirely on when you ask. The immediate reaction is anger and defense; the long-term reaction must be a return to the pursuit of peace. The challenge for leadership is to navigate the immediate pain without losing sight of the long-term necessity of coexistence.

The Courage to Show Up

True partnership is proven by presence. A poignant moment in their friendship occurred when Ner-David visited the Arab town of Tamra to pay condolences after a missile strike killed local women. In an atmosphere where social media was rife with divisiveness, the physical act of showing up—of a Jewish Israeli mourning with Arab neighbors—was a radical act of humanity.

The Responsibility of the "Fellow"

The concept of "fellowship," specifically within the context of the Aspen Institute, implies a higher standard of societal responsibility. It posits that those who have been blessed with success and cross-cultural understanding have an obligation to lead.

Moving from Success to Significance

Referencing the late Keith Berwick, a mentor to both, the dialogue centers on the transition from personal success to societal significance. It is insufficient to be a successful entrepreneur if the society around you is crumbling. The blessings of understanding the "other" come with the burden of action.

Ner-David argues that high-minded individuals often avoid politics because it is viewed as "dirty." However, abdicating the political arena leaves critical decisions in the hands of those who may not share values of empathy and coexistence. To create sustainable change, civil society leaders must engage with political power structures.

"If we don't also get our hands dirty on the political side, then we'll do a lot of the people's stuff which is important, but then terrible things will get committed by the political leadership."

Conclusion: The Inescapable Interdependence

The conversation between Jacob Ner-David and Forsan Hussein ultimately circles back to a single, undeniable fact: neither people is leaving. The destinies of Israelis and Palestinians are inextricably linked. The choice, therefore, is not between winning and losing, but between a future of perpetual conflict or a difficult, shared journey toward accommodation.

Drawing inspiration from their children and the desire to break the cycle of violence, they reject the luxury of despair. Optimism, in this context, is not a naive belief that things will easily get better, but a disciplined strategy. It is the refusal to let the darkest moments define the future. As they navigate the complexities of their region, their partnership stands as a testament to the idea that while politicians sign treaties, it is the people who must ultimately make peace.

![This New Bitget Platform Changes the Game [Literally Gold]](/content/images/size/w1304/format/webp/2026/02/bitget-launches-universal-exchange-gold-usdt.jpg)