Table of Contents

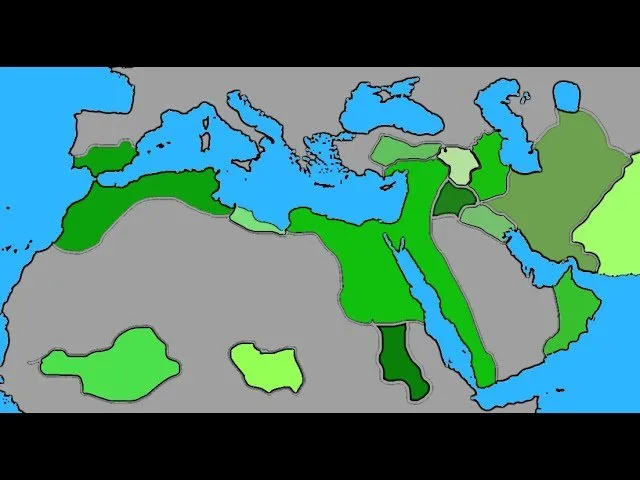

The decline of medieval Islam is a period of history that often exists in our collective psychological shadow. If you were to prioritize historical eras, most would gravitate toward World War II, the Civil War, or the Fall of Rome, leaving Islamic history as a footnote. This is a profound oversight. The trajectory of medieval Islam serves as a "twisted mirror" to Western civilization—the two are the closest siblings among major world civilizations, yet they took radically different paths.

To understand this era is to understand a combination of the "Fall of Rome" dynamic mixed with the stagnation often seen in Eastern societal cycles. At the beginning of the medieval period, the Muslim world shared many similarities with the modern West: it was cosmopolitan, scientifically advanced, and economically robust. By the end, it had fossilized into a traditionalist structure that would see little social differentiation until the era of European colonialism. Unpacking this decline reveals critical lessons about the fragility of intellectual freedom, the mechanics of empire, and the consequences of prioritizing orthodoxy over innovation.

Key Takeaways

- The "Twisted Mirror" of Civilizations: Islam and the West share deep roots, but while Europe eventually embraced the Enlightenment and dynamism, the Islamic world turned toward static traditionalism following its own "Fall of Rome" equivalent.

- Strategic Tolerance vs. Ideological Conformity: Early Islamic tolerance was largely a pragmatic necessity of ruling over vast Christian and Persian majorities; as Muslims became the demographic majority, the society shifted toward stricter intolerance and homogeneity.

- The Al-Ghazali Turning Point: The philosophical shift spearheaded by Al-Ghazali moved the culture away from rationalism and causality toward a mystical occasionalism, effectively stifling the scientific method for centuries.

- The Cycle of Dynasties: Historian Ibn Khaldun identified a recurring cycle where vigorous "barbarian" nomads conquer decadent urban centers, only to become decadent themselves within four generations, creating a perpetual loop of instability.

- Trauma of External Conquest: The devastation wrought by the Mongol invasions and the economic shifts caused by the Crusades traumatized the collective psyche of the region, leading to a defensive retreat into religious fundamentalism.

The Rise of the Arab Empire and the Strategy of Tolerance

The narrative of early Islamic conquest is often misunderstood through modern lenses of multiculturalism. The initial expansion was not driven by a desire for diversity, but by the necessities of a minority ruling class managing a vast empire.

- The "VC Capital" Model of Conquest: Arab military strategy operated similarly to venture capital. Charismatic warlords would build a following, raid a territory to test its defenses, and then partition the spoils. This allowed a relatively small population from the Arabian Peninsula to conquer the known world from the Atlantic to India.

- Dependency on Conquered Peoples: Upon conquering regions like Syria, Egypt, and Persia, the Arabs were effectively a warrior caste with limited administrative experience. They relied entirely on existing Christian and Persian bureaucracies to run the state, necessitating a policy of tolerance.

- Demographic Tipping Points: Tolerance was a strategy of survival, not benevolence. Once Muslims reached a demographic tipping point (becoming the majority around 1000 AD), the dynamic shifted from assimilating the conquered to standardizing the population, leading to stricter enforcement of Sharia and social restrictions.

- The Persian Influence: While the initial conquest was Arab, the administrative and cultural engine quickly became Persian. The shift from the Umayyad to the Abbasid Caliphate represented a transition from Syrian-Christian influence to Iraqi-Persian dominance.

- Urban vs. Nomad Dynamics: The tension between the desert nomads (Bedouins/Berbers) and the settled town dwellers became a defining feature of the civilization. The Prophet Muhammad was unique in his ability to unify these disparate groups under a single belief structure.

- Historical Revisionism on "Golden Age" Tolerance: Modern narratives often cite this era's tolerance as proof of moral superiority. However, primary sources reveal that restrictions on Christians and Jews—such as bans on building new churches or dietary restrictions—were consistently applied to maintain the distinct superiority of the ruling Islamic class.

"When studied improperly, [this time period] comes across as terrifyingly boring, but when studied correctly, it's one of the most interesting eras of history."

The Golden Age: Rationalism vs. The Incoherence of Philosophers

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of extraordinary intellectual flourishing, but it contained the seeds of its own demise. A fierce internal battle raged between the Mutazila (rationalist freethinkers) and the growing forces of religious orthodoxy.

- The Polymath Tradition: The era produced "Renaissance men" centuries before the European Renaissance. Figures like Al-Khwarizmi (algebra), Al-Razi (medicine), and Ibn al-Haytham (optics) pushed the boundaries of human knowledge, often integrating Greek philosophy with Islamic thought.

- The Role of Al-Ghazali: Perhaps the most pivotal figure in this decline was Al-Ghazali. While a noble figure attempting to save his society from what he viewed as moral decay, his work The Incoherence of the Philosophers effectively argued that rationality could not supersede divine revelation.

- The Death of Causality: Al-Ghazali’s theological victory established that cause and effect were not natural laws but the direct will of God. This philosophical stance undermined the foundation of scientific inquiry; if God wills every specific outcome, searching for physical laws becomes futile.

- Suppression of the Mutazila: The rationalist Mutazila school, which dominated the early Abbasid courts, was gradually purged. They had argued for a created Quran and the application of Greek logic to scripture—positions that were eventually deemed heretical by the rising Asharite orthodoxy.

- Shift to Legalism and Mysticism: As philosophy withered, intellectual energy was redirected toward two poles: hyper-legalistic interpretation of Hadiths (Sharia) and Sufi mysticism. The legalists built a rigid social cage, while the mystics provided an emotional escape, neither of which encouraged material or scientific progress.

- The Loss of the "Hermetic" Potential: There was a moment where Islam cultivated a worldview compatible with the precursors of modern science—alchemy, rational materialism, and free-market capitalism. The defeat of these "hermetic" forces by religious reactionaries is a critical turning point where Islam diverged from the trajectory that later led Europe to global dominance.

Political Decay and the Ibn Khaldun Cycle

Political stability in the medieval Islamic world was famously fragile. The historian Ibn Khaldun, writing in the 14th century, observed a distinct cycle of dynastic rise and fall that plagued the region.

- The 120-Year Cycle: Ibn Khaldun theorized that dynasties last roughly four generations. A vigorous nomadic group conquers a city, the second generation rules wisely, the third becomes complacent and imitates the culture of the conquered, and the fourth descends into total degeneracy, inviting a new wave of barbarians to restart the cycle.

- The Mamluk Phenomenon: To bypass the unreliability of tribal levies, Islamic rulers began importing slave soldiers (Mamluks), usually Turks or Circassians. These cohesive military castes eventually realized they held the real power, frequently overthrowing the Caliphs and establishing rapacious military juntas that had no organic connection to the populace.

- The Fragmentation of the Abbasids: The centralized Abbasid Empire did not collapse in a single dramatic event but slowly disintegrated. Peripheral territories like Spain, North Africa, and Persia broke away under local dynasties or foreign adventurers, turning the Caliph into a figurehead.

- Destruction of the Free Market: As military regimes like the Mamluks in Egypt grew more insecure, they turned to extortion. They implemented disastrous economic policies, such as 80% tariffs on Red Sea trade and state monopolies, destroying the vibrant capitalist class that had driven the early Golden Age.

- The Berber Dynasties: In the West (Maghreb and Spain), the cycle played out through Berber groups like the Almoravids and Almohads. These began as religious fundamentalist movements from the desert/mountains, sweeping into the cities to "purify" the decadent elite, only to become decadent themselves.

- State Formation Issues: The Islamic world struggled to form stable nation-states because loyalty was fractured between the universal Ummah (religious community), the tribe/clan, and the local region. Unlike Europe, which developed a stable landed nobility, the Middle East oscillated between weak urban merchants and transient military dictators.

"Al Gazali... was the turning point where Islam turned and if Islam had gone on the west's trajectory that's an event equivalent to communism never happening."

Trauma and the External Shocks: Mongols and Crusaders

While internal decay was the primary driver of decline, external shocks accelerated the process, inflicting deep psychological scars that pushed the civilization toward defensive conservatism.

- The Mongol Catastrophe: The Mongol invasions were not just military defeats; they were existential traumas. The destruction of Baghdad in 1258, the obliteration of irrigation networks in Persia, and the massacre of millions depopulated the region and shattered the confidence of the Islamic world.

- Loss of the Mediterranean: By the 11th century, the Mediterranean transitioned from a "Muslim Lake" to a sea dominated by Italian city-states. This economic shift, cemented by the Crusades and the Norman conquest of Sicily, isolated the Islamic economies from the lucrative trade that eventually fueled the European Renaissance.

- The Psychological Impact of Defeat: For a civilization that viewed itself as God’s chosen community (Dar al-Islam), repeated defeats by "pagan savages" (Mongols) and "barbarians" (Franks) created a crisis of faith. The societal response was to assume God was punishing them for straying from the text, leading to a doubling down on fundamentalism.

- The "Sensitive Young Warlord" Archetype: In the chaotic period following the Mongol invasions, a specific leadership archetype emerged—men like Tamerlane, Babur, and Shah Ismail. These figures combined extreme brutality with high culture, writing poetry and studying philosophy while building towers of skulls. It represented a desperate, violent vitality in a dying system.

- The Gunpowder Resolution: The chaos of the medieval period eventually stabilized into the three great "Gunpowder Empires" (Ottomans, Safavids, Mughals). However, this stability came at the cost of dynamism. These empires enforced rigid orthodoxies and bureaucratic control to prevent the chaos of the past, effectively freezing social evolution.

- Retreat from the World: Following these traumas, the intellectual curiosity that defined the Golden Age evaporated. The civilization turned inward. Philosophy was viewed with suspicion, and innovation (Bid'ah) became synonymous with heresy in the religious lexicon.

Conclusion: The Legacy of Stagnation

The decline of medieval Islam was not a single event but a slow-motion tragedy of choices and circumstances. The civilization that once translated Aristotle and invented algebra eventually succumbed to a worldview that prioritized stability over inquiry and tradition over progress. This historical trajectory explains much of the modern Middle East's struggle with statehood and modernity.

Just as the West's rise was not inevitable, neither was Islam's decline. It was the result of the triumph of legalistic orthodoxy over philosophical openness, the destruction of the middle class by military castes, and the psychological retreat caused by external invasions. Understanding this era provides a crucial context for the geopolitical realities of today, reminding us that civilizations are fragile constructs that require constant maintenance of their intellectual and economic foundations to survive.

![This New Bitget Platform Changes the Game [Literally Gold]](/content/images/size/w1304/format/webp/2026/02/bitget-launches-universal-exchange-gold-usdt.jpg)