Table of Contents

Professor David Kang reveals why East Asian nations peacefully coexisted for centuries while Europe fought constantly, and what this history teaches us about managing U.S.-China competition and Taiwan tensions today.

Key Takeaways

- For over 1,500 years, East Asian powers chose peaceful coexistence over constant warfare despite having massive military capacities

- Great power transitions in Asia typically occurred from internal collapse rather than external conquest - empires died from "suicide not murder"

- China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam developed a shared cultural vocabulary through common script, bureaucracy, and Confucian governance that enabled stable relations

- The Song Dynasty's fall to the Mongols resulted from strategic mistakes and obsession with reclaiming lost territory, not inevitable power transition dynamics

- Modern Asian nations aren't forming anti-China balancing coalitions because they must "live with China" regardless of American presence

- Taiwan represents the collision between traditional tributary relationships and modern Westphalian nation-state concepts

- China's current interests are largely "trans-dynastic" - inherited from previous regimes rather than uniquely Communist expansionist goals

- The successful Taiwan status quo has allowed all parties to prosper while avoiding the binary choices that typically lead to conflict

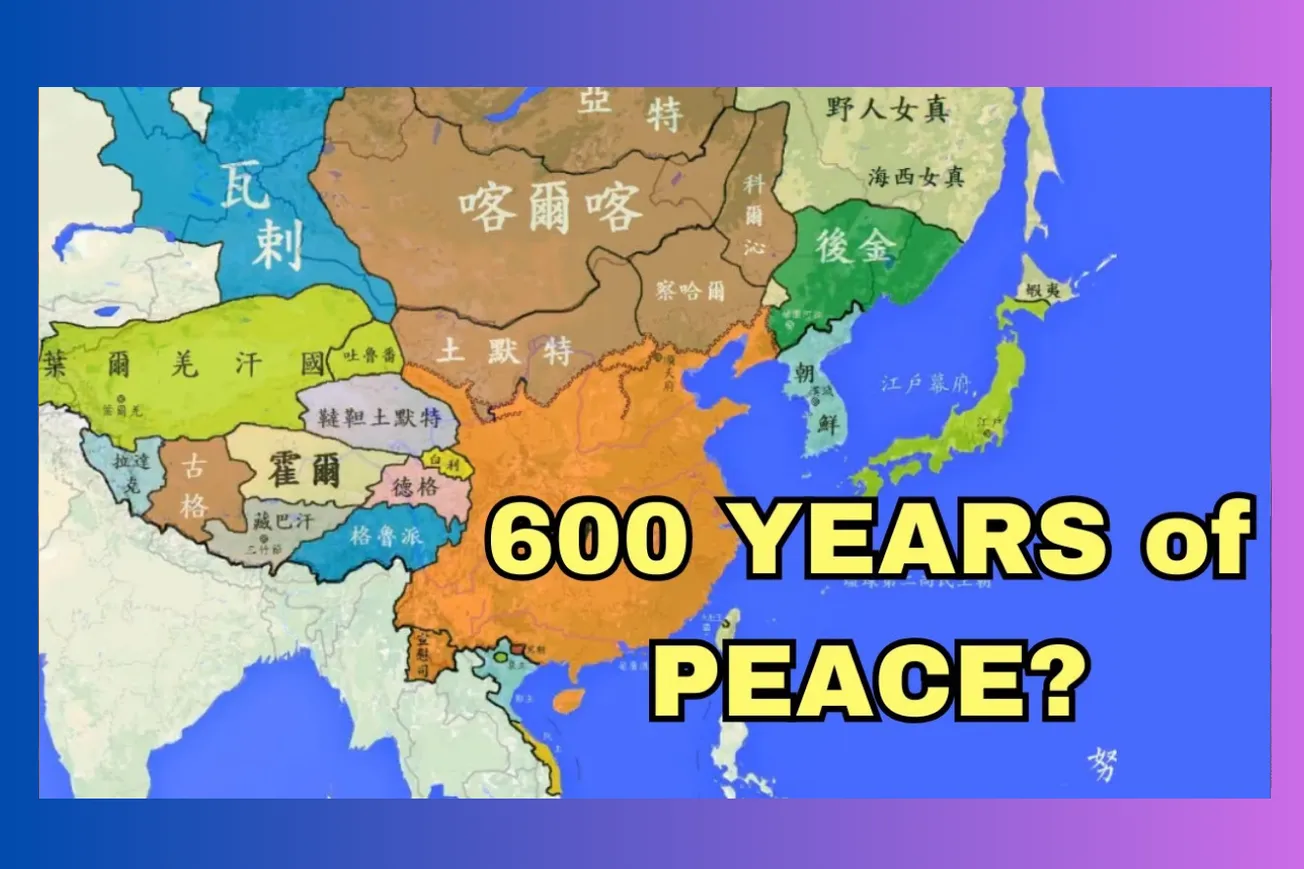

The Great Peace: Why Asia Didn't Fight Like Europe

The most striking revelation from David Kang's research is how fundamentally different East Asian international relations were from the European experience that dominates our thinking about great power competition. While medieval and early modern Europe saw near-constant warfare between roughly equal powers, East Asia achieved remarkable stability despite having nations with enormous military capabilities.

"If you had actually started studying international relations and you didn't start with Europe and you started with Asia, you would never come up with a theory of power transitions of rising and falling powers grabbing land," Kang explains. "Instead you'd come up with the theory of a bunch of really stable countries that have very clear conceptions of their own national identity."

This wasn't because Asian powers lacked the capacity for warfare. The scale of conflict when they chose to fight dwarfed European capabilities. During the Imjin War (1592-1598), Japan deployed 300,000 troops and 700 ships to invade Korea - "5 to 10 times what you could even think" possible in Renaissance Europe. For comparison, the famous Spanish Armada four years earlier involved only 20,000 troops and 130 ships.

Why East Asian peace endured:

- Shared Cultural Framework: All major powers used Chinese script, Confucian bureaucracy, and civil service examinations

- Common Vocabulary: 60-70% of vocabulary in Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese derived from Chinese

- Mutual Recognition: Each power had clear conceptions of their distinct identities while acknowledging unequal but legitimate relationships

- Hegemonic Stability: China's consistent dominance created predictable hierarchy rather than competitive anarchy

- Internal Focus: Dynastic transitions typically resulted from domestic rebellion rather than foreign conquest

The stability stemmed from what Kang calls a "common conjecture" - shared understanding of how international relations should work. "Both sides Japanese Koreans Vietnamese and Chinese had a common vocabulary literally a common vocabulary and an understanding of what mattered what didn't matter how to interact with each other."

The Song Dynasty's Strategic Blindness: Lessons in Misplaced Priorities

The Song Dynasty's fall to the Mongols (1279) offers a masterclass in how great powers can destroy themselves through strategic myopia rather than inevitable decline. At its height, Song China had 50 million people, a three-million-man army, and was "an incredibly powerful country that had come up with all this flourishing" including paper money and advanced canal systems.

The Mongols, by contrast, had perhaps one million people total. "There's just no way that this was a rising power and a falling power," Kang argues. Instead, the Song made a series of catastrophic decisions driven by emotional attachment to "lost" territories rather than rational threat assessment.

The Song's fatal error was prioritizing the recovery of the "16 prefectures" - territory lost to the Liao Dynasty - over addressing the obvious Mongol threat. "The song had decades of evidence that the Mongols were the real threat but they worked with them because they were trying to get this territory back."

The Song's strategic mistakes:

- Misidentified Threats: Focused on reclaiming territory from weaker neighbors while ignoring existential danger

- Alliance with Wolves: Partnered with Mongols against Liao, "letting the fox into the hen house"

- Emotional Decision-Making: Pursued "honorable reclamation" of ancestral land despite changing strategic realities

- Ignored Intelligence: Decades of evidence about Mongol expansion failed to change strategy

- Internal Obsession: More concerned with territorial completeness than actual security

This pattern of powers focusing on "what China should be" rather than external threats resonates with contemporary concerns about nations becoming obsessed with historical grievances while missing larger strategic shifts.

The Tributary System: Hierarchy Without Conquest

The key to East Asian stability was the tributary system - a hierarchical but non-imperial arrangement that allowed smaller powers to maintain autonomy while acknowledging China's preeminence. This system challenges Western assumptions about how great powers behave when they have overwhelming advantages.

Vietnam provides the clearest example. After gaining independence around 1079, Vietnam "instantly engaging in tribute relations with China at the time song." The border negotiated then "is literally in the same place today" - nearly a thousand years of stability marked by "two bronze pillars" that still define the frontier.

Korean diplomats mastered this system by convincing Chinese emperors that respecting Korean autonomy was actually the most imperial thing to do. As one scholar quoted in Kang's book observes: "Korean envoys and memorial drafters use this notion of the moral empire... to convince empires and their agents that behaving according to Korean expectations was the best way to be imperial."

How the tributary system worked:

- Symbolic Hierarchy: Smaller powers acknowledged Chinese suzerainty without surrendering sovereignty

- Mutual Benefit: China gained prestige and stability, smaller powers gained protection and trade access

- Flexible Implementation: Relationships adjusted to changing circumstances while maintaining basic framework

- Cultural Integration: Shared Confucian values created common language for negotiation and conflict resolution

- Practical Autonomy: Tributary states maintained independent domestic policies and many foreign relations

This system's success contradicts realist predictions that hegemonic powers will maximize their control over weaker neighbors. Instead, China often chose restraint when conquest was clearly possible.

The Imjin War: When the System Broke Down

The Imjin War (1592-1598) represents the most significant breakdown of East Asian stability and offers crucial insights about what happens when the normal rules stop working. Japan's invasion of Korea, intended as a stepping stone to conquering China, violated every assumption about how regional powers should behave.

The war's scale was unprecedented for its time. "300,000 Japanese troops, 700 ships - the scale of the war was 5 to 10 times what you could even think... in Europe at that time." Yet the conflict also demonstrated the system's resilience and the unusual restraint that continued even during wartime.

Most remarkably, when Chinese forces helped repel the Japanese invasion, they voluntarily withdrew from Korea despite total military control. "All the Chinese had to do was say okay we're in charge... but within about a year they all went home... this isn't our country this is Korea okay good luck with that."

Why the Imjin War was exceptional:

- Domestic Disruption: Japan's century of internal warfare created unique pressures for external expansion

- Lack of Reconnaissance: Hideyoshi made no serious assessment of relative power or strategic feasibility

- Violation of Norms: The invasion shocked Korea and China, who initially refused to believe it was happening

- System Resilience: Despite massive disruption, normal relationships resumed after Japanese withdrawal

- Restraint in Victory: China's voluntary withdrawal demonstrated continued commitment to traditional boundaries

The war's aftermath reinforced rather than undermined the traditional system. Japan "form the Tokugawa Shogunate for 200 years they don't do anything... for 300 years these countries then just sort of interacted with each other." It was "the only war between Japan Korea and China in 600 years."

Quote Analysis: Internal Collapse vs. External Conquest

Two key quotes from Kang's interview capture essential insights about how great powers actually fall and why East Asian history matters for contemporary policy:

"Empires die from suicide not murder... every single dynasty transition in East Asia came from internal reasons when one of the dynasties collapsed or decayed or there was a rebellion. Remarkably few changed because of external invasion."

This observation fundamentally challenges power transition theory's emphasis on external military threats. Throughout East Asian history, the Korean dynasties (Silla, Koryo, Choson), Japanese regimes (Kamakura, etc.), Vietnamese dynasties, and even Chinese empires (Tang, Ming, Qing) all fell due to internal problems rather than foreign conquest. Only the Song's defeat by the Mongols represents external conquest, and even then, internal strategic mistakes enabled the outcome. This pattern suggests that contemporary China's domestic challenges - economic slowdown, demographic decline, social tensions - may matter more than U.S.-China military competition.

"Asian countries do not want to do that [choose sides completely]... they have to live with China they don't have to like it but they have to craft a relationship with this massive country and that's what they did back then."

This quote explains why American expectations of anti-China balancing coalitions consistently fail to materialize. Asian nations face geographical and economic realities that make total separation from China impossible, regardless of security relationships with the United States. Vietnam joining BRICS, Thailand's growing ties with China, and South Korea's careful balancing all reflect this fundamental constraint. The historical precedent suggests that even close U.S. allies will maintain working relationships with China because "nobody's going away" - the same logic that enabled centuries of stability in East Asia.

The Western Frontier Exception: Why Some Territories Were Different

Kang's analysis reveals a crucial distinction between China's eastern and western frontiers that helps explain why some territories were conquered while others remained independent. The pattern wasn't random - it reflected fundamental differences in how societies organized themselves and related to Chinese civilization.

On the eastern frontier (Korea, Japan, Vietnam), China faced "recognizably states" with "bureaucratically administered" governments, written languages using Chinese script, and political systems that consciously emulated Chinese models. These societies wanted what China had and could communicate in shared cultural terms.

The western frontier presented different challenges. Nomadic peoples "didn't want what the Chinese wanted. These are incompatible worldviews and they knew it." The material basis of steppe life - extensive grazing requiring constant movement - made sedentary bureaucratic government impossible. "If you decided this lifestyle which is that you're going to live from grass energy you are just going to fundamentally want to have a nomadic lifestyle."

Eastern vs. Western Frontier Dynamics:

- Eastern Powers: Sedentary agriculture, bureaucratic government, Chinese script, Confucian values, compatible worldviews

- Western Peoples: Nomadic pastoralism, tribal organization, oral tradition, steppe values, incompatible lifestyles

- Eastern Relations: Tribute, diplomacy, cultural exchange, stable borders

- Western Relations: Raids, walls, military campaigns, shifting frontiers

This distinction explains why Tibet and Xinjiang were eventually incorporated while Korea, Vietnam, and Japan remained independent. The nomadic territories couldn't maintain the kind of state-to-state relationships that characterized eastern diplomacy.

Modern Parallels: Taiwan and the Westphalian Problem

The Taiwan issue crystallizes the collision between traditional East Asian international relations and modern Westphalian concepts of sovereignty. In the traditional system, Taiwan's status would be easily managed through some form of autonomous arrangement acknowledging Chinese suzerainty while preserving local self-governance.

"The only reason Taiwan is an issue is that we have decided that there's only one legitimate type of polity which is called a nation state that gets recognition and has a seat on the blah blah blah," Kang explains. "The easiest way to sort this out is to simply not be Westphalian and say they can be this thing."

But the modern international system requires binary choices that the traditional system avoided. Taiwan must be either independent or part of China; there's no recognized middle ground despite centuries of successful precedents for ambiguous arrangements.

Taiwan's Historical Uniqueness:

- Late Development: Taiwan's indigenous peoples never developed the bureaucratic state systems that enabled diplomatic relations

- Colonial History: Unlike Korea or Vietnam, Taiwan lacked continuous independent political development

- Strategic Ambiguity: Current status quo successfully manages competing claims through deliberate vagueness

- Westphalian Trap: Modern sovereignty concepts make traditional solutions impossible

Kang argues the current status quo actually works well for all parties: "Taiwan has gotten rich, China has gotten rich, we have bought lots of cheap really well produced goods." The problem is pressure to resolve ambiguity that has enabled prosperity and peace.

The Trans-Dynastic Continuity of Chinese Interests

One of Kang's most important insights concerns the continuity of Chinese foreign policy goals across different political systems. Rather than representing uniquely Communist expansion, most of China's current international objectives are "trans-dynastic" - inherited from previous regimes including the Qing Dynasty and Kuomintang.

"Almost every single main Chinese foreign policy interest or agenda or purpose is what I'm calling trans-dynastic," Kang argues. "None of it is new." Taiwan is the clearest example: "The Qing explicitly were saying don't take this Japan or else our relations will be poisoned forever. This is not new this is old."

This continuity challenges narratives about Communist China as uniquely expansionist. Instead, current Chinese policy appears focused on recovering territories considered historically Chinese rather than pursuing unlimited expansion. "I have never seen that's one reason... you do not see that now... I don't see a whole lot of thought of well we got once we get Taiwan then let's take Japan."

Trans-Dynastic Chinese Interests:

- Taiwan: Qing Dynasty priority inherited by Republic of China and PRC

- Hong Kong: 1841 colonial loss that remained unresolved grievance across regimes

- South China Sea: Historical claims predating Communist rule

- Border Territories: Disputes with India, Russia trace to imperial-era boundaries

- Territorial Integrity: Consistent priority across different political systems

This pattern suggests Chinese behavior is more predictable and limited than often assumed - focused on historical grievances rather than unlimited expansion.

Why Asian Balancing Against China Isn't Happening

American policymakers consistently expect Asian nations to form balancing coalitions against China, but this expectation reflects European rather than Asian historical patterns. "The countries in Asia are not going to join a US containment coalition against China. That's not how it's going to work," Kang argues.

The fundamental difference is that Asia has always been a hegemonic rather than multipolar system. "Europe was a balance of power system... Asia has and is a hegemonic system it's got one massive power and a bunch of smaller countries." These systems operate according to different logics.

Evidence for this includes declining military spending across the region despite China's rise, continued economic integration with China even among U.S. allies, and the universal reaffirmation of "One China" policies after Nancy Pelosi's Taiwan visit. Even South Korea, a treaty ally, refused to meet Pelosi at the airport after her Taiwan stop.

Why Asian Balancing Fails:

- Geographic Reality: Asian nations can't relocate away from China regardless of security preferences

- Economic Integration: Trade relationships with China matter more than ideological alignment

- Historical Experience: Centuries of successful accommodation with Chinese hegemony

- Limited Threats: Asian nations don't perceive existential threats from China requiring military responses

- Hedging Strategies: Maintaining relationships with both China and the U.S. rather than choosing sides

This doesn't mean Asian nations love China or will always defer to its preferences, but rather that they approach the relationship as a permanent reality requiring management rather than a threat requiring elimination.

Internal Dynamics Trump External Competition

Kang's most important policy insight concerns the relative importance of internal versus external factors in determining great power behavior. History suggests that "when Xi Jinping wakes up in the morning is he more concerned with what's going on internally or is he itching to make land grabs?"

The historical record strongly suggests internal dynamics matter more. Every major power transition in East Asian history resulted from domestic collapse rather than external conquest. This pattern appears relevant to contemporary concerns about both Chinese and American stability.

"I have spent my adult life hearing about the impending real estate crash in China," Kang notes, while simultaneously American politics shows increasing signs of internal stress. The question becomes whether domestic challenges will overwhelm external competition as the primary driver of great power behavior.

Internal vs. External Priorities:

- Historical Pattern: Dynasties fall from rebellion, corruption, economic crisis, not foreign invasion

- Contemporary China: Demographics, economic slowdown, social tensions as major challenges

- Contemporary America: Political polarization, infrastructure decay, social divisions

- Resource Allocation: Internal stability often requires more attention than external expansion

- Policy Implications: Domestic reform may matter more than military competition

This insight suggests that successful great power competition may depend more on internal renewal than external confrontation - a lesson from East Asian history that challenges conventional strategic thinking.

Looking Forward: Managing Great Power Competition in Asia

Kang's historical analysis offers several principles for managing contemporary U.S.-China competition without falling into the conflict patterns that characterized European great power relations:

- Respect Historical Patterns: Asian nations will hedge between great powers rather than choose sides definitively. Expecting exclusive alignments misreads both historical precedent and contemporary incentives.

- Distinguish Internal from External: China's most serious challenges are domestic, suggesting that competition should focus on internal renewal rather than external containment.

- Maintain Strategic Ambiguity: The Taiwan status quo works precisely because it avoids binary choices that typically force conflict. Pressure to resolve ambiguity may create the problems it seeks to prevent.

- Understand Trans-Dynastic Continuity: Chinese objectives reflect historical grievances rather than unlimited expansion, suggesting they may be more predictable and manageable than often assumed.

- Recognize Limits of Power: Even hegemonic powers like China historically showed restraint when conquest was possible, suggesting that overwhelming power doesn't inevitably lead to unlimited expansion.

The East Asian historical experience suggests that great power competition can be managed through accommodation and restraint rather than inevitable military confrontation. The key is understanding that different regions may require different approaches based on their historical patterns and cultural frameworks rather than assuming European models apply universally.

This doesn't guarantee peace - the arrival of Western imperial powers in the 19th century disrupted traditional patterns and created new forms of conflict. But it does suggest that war between great powers isn't inevitable if leaders understand and respect the historical patterns that have enabled stability in the past.

The ultimate lesson from Asia's great power wars may be how rarely they actually occurred despite ample opportunity and capability. In a world facing nuclear weapons and global economic integration, this historical precedent for great power restraint may be more relevant than European examples of constant competition and conflict.

![This New Bitget Platform Changes the Game [Literally Gold]](/content/images/size/w1304/format/webp/2026/02/bitget-launches-universal-exchange-gold-usdt.jpg)